A Look At HSOC and Why It Should Be Dismantled

The Healthy Streets Operations Center (HSOC) grew out of the Mission Police Station in January 2018, with the goal of clearing all the tents from the Mission District. It almost succeeded in that endeavor. But rather than reducing homelessness, the number of folks on the streets actually increased in the district, as did the misery of those who had their flimsy shelter and the bit of dignity that tents provided ripped away.

This August, Department of Emergency Management (DEM) director Mary Ellen Carroll gave the quarterly HSOC presentation to the Local Homeless Coordinating Board. Carroll painted a picture of a team whose primary goal is to help unhoused people, using a service-led model driven by public health. She described a process of removing tents that involves gathering data on unhoused people, offering shelter alternatives and identifying those unhoused community members in need of more serious medical attention.

The Coalition on Homelessness has been present at many, if not most, of these operations since the inception of HSOC, acting as legal observers and peer support for those being displaced. What we have seen time and again is that HSOC’s operating procedures are not being followed. But even if they were, HSOC’s approach is highly problematic, trauma-inducing and likely to exacerbate homelessness. Because we have seen the impact of these operations on our most vulnerable community members, the Coalition on Homelessness is calling for the immediate dismantling of HSOC.

How Did We Get Here?

For decades, homelessness has been used as a political wedge in San Francisco elections, with politicians using enforcement to draw more conservatives and business interests to the ballot. As a result, our homeless response is inequitable and politically charged. One outcome is that the Homeless Outreach Team (HOT) has had its trust among unhoused community members greatly damaged through years of being sent out alongside police and Public Works staff who are conducting sweeps to “clear” areas that are of political importance or that draw the ire of elite San Franciscans, rather than being allowed the freedom to connect those most in need with the shelter options they want.

HSOC started as a police-led, complaint-driven coordination of city departments and resources designed to lower tent counts and break up large encampments. Later, in early 2019, the operations moved out of the police department and into the Department of Emergency Management, which oversees 911 response and leads the City’s COVID-19 response.

While HSOC’s leadership changed departments, its core purpose of moving people along hasn’t changed. For unhoused community members, the cycle of being shuffled around by the City and having belongings trashed continues uninterrupted. These operations make it harder for people to find places that are well lit, or near people with whom they feel safe. For people with no other options, tents offer a modicum of shelter and privacy, and take the edge off the indignity of living in public spaces. While HSOC sometimes offers services before clearing encampments, it often has very little to offer, and relies on police or Public Works to simply clear an area. After an area is cleared, HSOC often removes bathrooms and constructs barriers to prevent people from returning, further limiting safe sleeping areas for individuals who have no alternative.

This is an inherently flawed approach. While HSOC frequently boasts its success in reducing the number of tents in San Francisco, this success is not reflected in exits from homelessness. Tents are not people, and removing tents does nothing to change the housing status of the individual who slept in it, and it leaves people on the street with even less protection from the harsh conditions under which they live.

Beyond this, HSOC has also significantly changed how the City allocates resources. In order to justify its operations, HSOC reserves shelter beds and housing resources for people whose encampments are swept. This means that the thousands of unsheltered San Franciscans who are not targeted by a sweep, but are in a better position to accept available services, are shut out of those beds. These resources are often directed to the most politically important areas, rather than those most in need.

Traumatizing Operations

One way the Coalition on Homelessness works to ensure the human rights of those on the streets is through consistent monitoring of City operations that impact unhoused people, by sending staff and volunteers to talk to the people who are targets of sweeps. Our monitoring and outreach has concluded that the reality of ground operations is significantly divorced from what is described in public-facing documents.

Instead of encampment operations being based on the needs of people living on the streets, they are driven by the complaints of housed individuals. Even so, the City doesn’t have enough shelter beds for the people they displace through sweeps. Our monitoring and reviews of internal HSOC emails reveal that shelter beds are only available for a fraction of encampment residents. Folks without viable options find themselves further destabilized and with nowhere to go. This contradicts what Director Carroll reported publicly when she said, “If we do not have enough shelter beds, we do not carry out the operation.”

Public Works is supposed to follow its own “bag and tag” protocol, confiscating only unclaimed property and leaving a notice of where to pick it up. But on the ground, we have seen that the protocol is not followed in practice. Property is confiscated even as homeless people rush to gather their belongings, and we regularly field reports of stolen survival gear, medications and cherished personal items. Once property is confiscated, it can be impossible to retrieve it, as much of it is trashed instead of stored. We also see a clear connection between overdoses and the confiscation of Narcan during sweeps. When the City illegally confiscates property, it is not only inhumane—it is often fatal.

Where Do People Go?

In her August report to the Local Homeless Coordinating Board, Director Carroll shared cumulative numbers of placements for folks displaced by sweeps. These numbers have been removed from public documents, but we were able to screen shot them during the live streamed presentation. The numbers focused almost entirely on success in removing tents. In total, HSOC stated that it encountered 4,648 “clients” between June 10, 2020 and June 30, 2021, and only 2,077, or 45%, were “placed.” These numbers reveal a jarring and systemic failure: More than half of encampment residents were displaced to another street corner. Of those who were “placed,” 57% were sent into congregate shelters or sanctioned encampments. About 40% were put in SIP hotels, which were made available for a very limited time.

As we move through encampment sites, our outreach team asks residents whether they were offered any services, and if so, which. The majority report that they had not been offered services, while some folks said they were offered congregate shelter. HSOC claims that currently, the “acceptance rate” of services is only 30%. This number is highly suspicious, but it’s also important to understand that the prevailing wisdom among service providers is that “service resistance” is a myth. When individuals do not “accept” services, it is a system failure: the offer itself is not meeting the need. Even outside a pandemic, placing individuals in congregate shelter is often inappropropriate for a variety of reasons, including because they often lack disability accommodations. But as the delta variant ravages our communities, it is not difficult to grasp why someone might turn down an offer to stay in a large facility full of strangers.

“They offer shelter,” a former HOT staff person told us. “But everyone at HSOC knew that staying at MSC South would be more harmful physically and mentally than staying in the tent and they did it anyway. There are no ethical guidelines there.”

Conversely, during the window when hotel rooms were made available, the acceptance rates of SIP hotels was about 95%. Hotels offered bathrooms, privacy and dignity. This acceptance rate further demonstrates that when the system responds to the needs of unhoused people, it can easily move people off the streets.

Unfortunately, SIP hotels were made available primarily to individuals who were being swept out of encampments, leaving in the dust those whom public health employees and other front-line service providers identified as most in need. In other words, if you were lucky enough to live in a tent surrounded by others in tents, you got a hotel room. If you were so destitute that you didn’t even own a tent you were mostly screwed.

The Shifting Ground of National Standards

In 2021, communities and governments nationwide are re-examining a police response to homelessness. The federal government now penalizes municipalities in McKinney Act funding applications for failing to abate criminalization, and the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness has created guidelines for cities to move away from sweeps and instead to collaborate with communities in relocating individuals to permanent housing. If permanent housing is not available, the guidelines suggest moving folks into temporary settings. The Obama administration’s Department of Justice statement of interest in Martin v. Boise spelled out that it is a form of cruel and unusual punishment to enforce laws against camping, sitting and lying to those who are unhoused when no adequate shelter is available. The unhoused plaintiffs prevailed in the lawsuit.

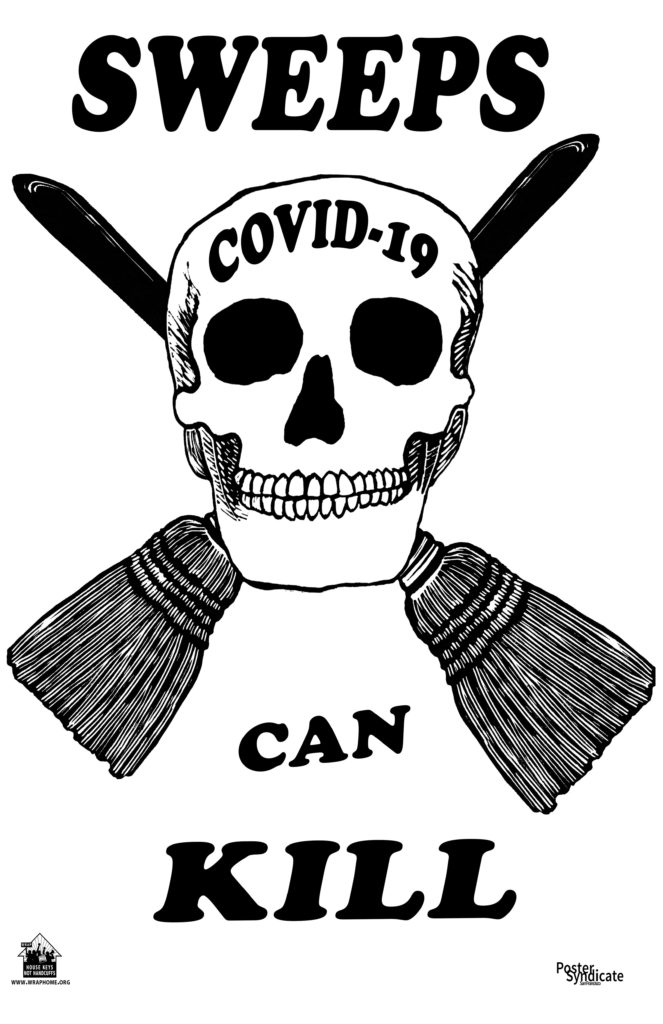

The virus that causes COVID-19, and now its delta variant, makes displacing and criminalizing unhoused community members even more egregious. Congregate settings are currently not considered a safe option due to individual medical risks and public health risks. The CDC’s Interim Guidance on Unsheltered Homelessness and Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) for Homeless Service Providers and Local Officials states that if there are no available housing resources for individuals then cities should “allow people who are living unsheltered or in encampments to remain where they are” to prevent the spread of infectious disease.

The shifting policies of the above institutions illustrate a growing recognition of the failure of policing our way out of homelessness and the need for a different strategy to address the growing crisis. So why, in 2021, is San Francisco still championing a police response to homelessness, led by HSOC?

Going Forward

The very structure and intent of HSOC is deeply flawed. A focus on tent removal means that its work does not center on ensuring that the humans in the tents have a pathway off the streets. And the involvement of police in encampment operations guarantees a lack of trust from impacted communities. For these reasons, the Coalition on Homelessness has taken the position that HSOC should be dismantled.

We know from experience that encampments can be cleared with dignity and fairness. In 2012, San Francisco successfully carried out an “encampment resolution” at the King Street encampment in accordance with federal guidelines. After months of the City’s failed attempts to criminalize and displace the camp residents, Bevan Dufty, who was then the Mayor’s homeless director, got involved. He reached out to community advocates and camp residents for counsel, took their input to heart, and secured a church where the residents could relocate together, allowing them to stay with friends, partners and pets. He designated a storage container where belongings could be stored intact, and most importantly, created an exit plan for the church. After a stay in the church, residents were relocated to housing, with careful considerations for maintaining the relationships residents had developed through their experiences together.

This became especially important when Ian Smith, one of those residents and a contributing writer to Street Sheet, developed cancer. Thanks to the thoughtful relocation effort, Smith was able to spend the rest of his young life surrounded by friends who took care to preserve his writing and shower him with love in his last days. Throughout this process, there were no protests, and no roadblocks from the Coalition on Homelessness, because it was done right.

Going forward, any clearing of encampments should follow the precedent set in 2012. The property of encampment residents should be respected. The community should be brought in, not deliberately excluded. The City can begin by identifying a variety of new resources for individuals in an encampment, and then send HOT workers in to spend at least two weeks with encampment residents to deeply assess their needs. This should start by addressing garbage, water and medical needs so that assessment can occur without undue hardship. Police should not be involved. Paramedics should be called only if there is a medical emergency. Public Works should wait to clean until everyone is gone. And critically, given the history and trauma those in encampments have survived, there should be a system of accountability: All operations should be publicly posted and an independent human rights monitor assigned to witness every operation.

San Francisco can do this right. There is no excuse for forced relocation. As UCSF’s Dr. Margot Kushel has written in response on how to combat homelessness, “There is no medicine as powerful as housing.”