by Chris Herring

Since 2009 San Francisco has counted those in jail who identify as homeless as part of the annual point in time count. In the most recent count, released last month, the City counted 242 homeless adults in County jails—about 20% of the total jail population. This is more than double the number counted in 2013 (126), although less than the number counted in 2011 (317) and 2009 (394).

Since 2009 San Francisco has counted those in jail who identify as homeless as part of the annual point in time count. In the most recent count, released last month, the City counted 242 homeless adults in County jails—about 20% of the total jail population. This is more than double the number counted in 2013 (126), although less than the number counted in 2011 (317) and 2009 (394).

A point-in-time count on a single night of the year is no way to assess the overall homeless population, but we can safely say a few things from these numbers: First, on any given night, the jail holds more homeless people than are in the hospital or treatment programs combined. Second, there are typically just as many homeless people in the jail as there are in the city’s largest shelters, which have between 250 and 400 beds. Third, the point-in-time survey found that 30% of San Francisco’s homeless people had spent at least one night in jail during the past year. In short, the County jail is by any definition a primary institution of homeless management in the city of San Francisco.

SF Jail By the Numbers

| 10–24% | SF Jail inmates who are homeless on any given night. |

| 30% | Homeless people who spent at least one night in jail in the past year. |

| 44% | “Chronically” homeless people who spent at least one night in jail in the past year. |

| 22% | Homeless people who spent more than five days in jail. |

| 56% | SF jail population that is Black. |

| 85% | SF jail population has not been convicted of a crime. |

Source: Applied Survey Research, San Francisco’s 2013 Point in Time Count. 2013.

Much of this incarceration stems from the fact that San Francisco has more anti-homeless laws than any other city in California—23 ordinances banning sitting, sleeping, standing, and begging in public places—and is a national leader in criminalizing poverty. Political disputes over these laws are well known. But what often goes overlooked are the consequences of such laws on individual homeless people.

To understand the impact of San Francisco’s punitive approach to managing homelessness, the Coalition on Homelessness (also publisher of the Street Sheet) surveyed 351 homeless people about their experiences with criminalization under the supervision of researchers at the UC Berkeley Law School’s Human Rights Center. The findings show that San Francisco’s policy of incarcerating its poorest not only perpetuates homelessness for those already on the streets, but actually produces homelessness and more crime in the process.

Arrest and Incarceration: A Common Experience of Homeless People

Homeless people are more likely to be arrested because of numerous factors. Specifically, homeless people are

often in poor neighborhoods with higher levels of policing

targeted by special anti-homeless and “quality of life” provisions designed to entangle them

frequently searched and approached due to complaints against their very presence

caught in personal possession of drugs with greater frequency than those who use drugs in their own homes.

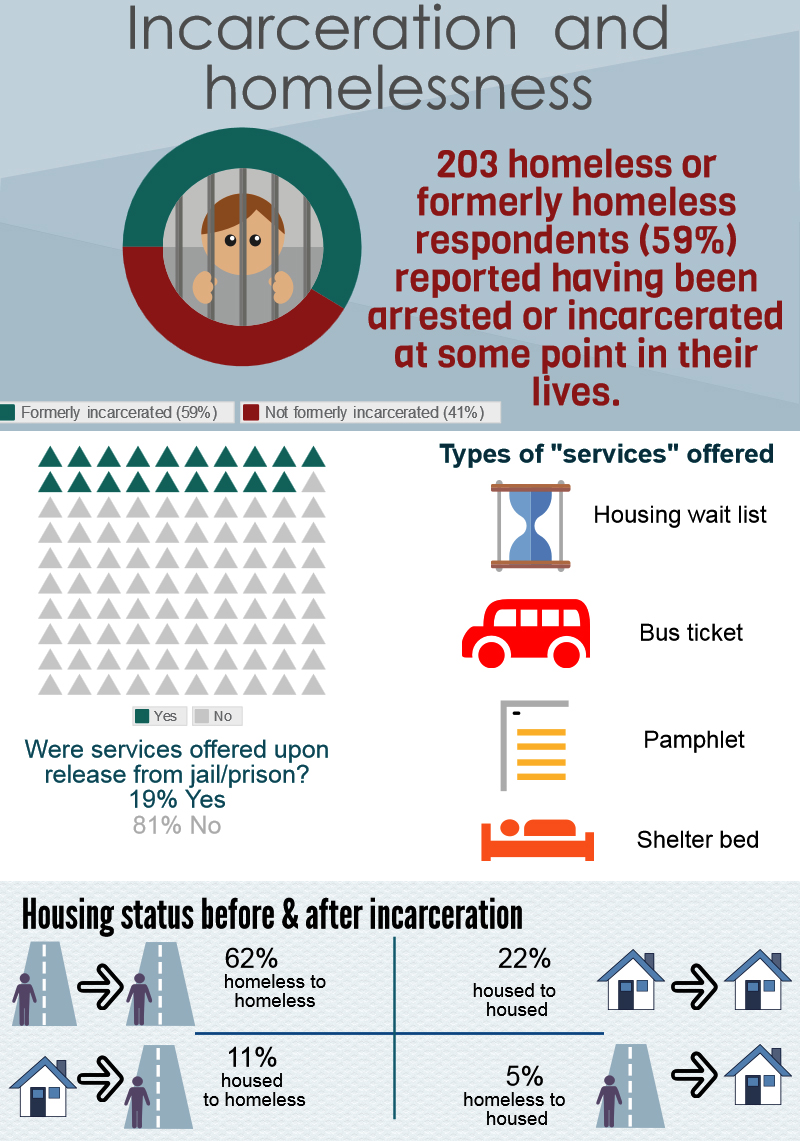

We found that the majority—59%—of survey respondents had experienced incarceration, and that 44% had been incarcerated multiple times, with their most recent incarceration having occurred within the last three years.

While surveyors did not ask respondents about the reasons for their arrests or incarcerations, we can infer from statistics on arrest and incarceration statewide and in San Francisco that the vast majority were for non-violent, poverty-related offenses.

Nearly 6,500 arrests in the state of California are attributable directly to anti-homeless laws. Most homeless respondents to the last point-in-time survey who had been incarcerated reported that they were in jail for five days or less.

The short duration of incarceration means that most homeless people who are in jail are there simply because they are too poor to afford bail. The San Francisco Public Defender reports: “85% of the roughly 1,300 inmates in county jail haven’t been convicted of anything. That’s more than 1,000 men and women. They are there not because they have been found guilty, but because they simply cannot afford bail.”

Short stays in jail not only entangle homeless people for longer periods of time due to their poverty, but also effectively un-house a number of people. Miles, a 51-year-old white man who camps, reported the impact of an arrest on his life: “When I got arrested last time, that was when my marriage ended… They didn’t let me call work to explain (what happened). It took me two and a half, three days to explain to work why I was MIA. I lost my job after that… It kicked off my divorce, which was the beginning of the end for me. I lost my house.”

A short period of incarceration can also be traumatic and disruptive, threatening physical and mental health. Z, a 22-year-old Black woman who stays in transitional housing, remembers being arrested and incarcerated after she defended herself against domestic violence.

“Emotionally, I felt so dead inside. You expected me to be a criminal… They took pictures of me when I came in… There was only a nurse with a Q-Tip… I’m in a holding cell. I’m locked up at this point, being treated like a dog… They kept me for four days, which included my birthday… (Later) I held up a sign reading ‘A citizen was falsely arrested. Zero investigation was done. I wonder what a civil rights lawyer would have thought about it?’ …I just experienced a PTSD moment in a domestic violence situation, and then I’m in jail like I’m a criminal.”

In effect, the San Francisco jail is warehousing poor and homeless people. The vast majority of people in jail in San Francisco have not been found guilty of a crime.

High bail amounts ensure that homeless people will remain in jail for minor offenses before they are even tried, often unable to finance the lowest $500 bond in bail, while wealthy people accused of more serious offenses are released. The use of bail exacerbates racial inequalities: Most people who are in the San Francisco jail because they’re too poor to afford bail are people of color, like Z. Because they cannot afford bail, the County incarcerates them at a cost of $173 per day.

Re-Entry: Homeless by Criminalization

While proponents of a “get tough” strategy believe that contact with law enforcement pushes homeless people off of the streets and into services, the data indicate that the opposite is true: Criminalization perpetuates extreme poverty.

Two thirds of respondents who reported being incarcerated were homeless at the time of arrest. Of these, fully 92% returned to homelessness after their release. However, one third of respondents reported being housed at the time of their last incarceration. Of this group, a significant portion, 34%, reported becoming homeless at the time of their release. In other words, while most survey participants’ housing status did not change as a result of incarceration, they were far more likely to end up homeless or lose their housing than they were to end up housed upon release.

According to the Re-entry Council’s Access and Connections Subcommittee, people who were poor prior to incarceration often leave jail with nowhere to go, and no way to access the social networks that supported them before arrest. The penal system rarely provides opportunities to connect with services or resources that can ameliorate poverty. Only 19% of survey participants who spent time in jail or prison were offered services upon release, compared to 81% who were offered nothing. Furthermore, in most cases, the “services” participants identified were minimal, and included things like “a bus ticket.”

To make matters worse, incarceration can cause people to lose their benefits such as General Assistance or Social Security, or to lose their health insurance.

Not only do homeless people who are incarcerated often lose their benefits, and only source of income, but incarceration also creates further barriers to getting a job, a key determinant of housing access on the private market. Most employers conduct background checks, and discriminate against prospective employees who have a criminal record. Even in states that have banned background checks, information about criminal history is often easily accessible online.

One year after release, 60% of formerly incarcerated people remain unemployed. Among those who are able to secure post-release employment, wages are an average of 40% lower than wages of someone with the same level of education who has never been incarcerated. This earnings gap persists throughout the formerly incarcerated person’s working life. Furthermore, a criminal record can disqualify one for various housing benefits. It is therefore not surprising that those who have been incarcerated—whether homeless at the time of arrest or not—are at high risk of homelessness upon release.

A New Policy Approach

One way to prevent both homelessness and incarceration of homeless people with disabilities is through provision of permanent supportive housing that offers voluntary harm reduction-based services. A number of studies have shown that increased investment in permanent supportive housing reduces costs related to hospitalization and incarceration—both expensive ways to respond to extreme poverty.

In 2001, San Francisco’s Budget and Legislative Analyst found that supportive housing resulted in significant net cost savings by reducing public costs related to incarcerating and providing emergency services for chronically homeless San Franciscans. In New York, a controlled study found that provision of supportive housing to homeless people with psychiatric disabilities resulted in less spending on the incarceration of members of this group.

Housing can break the cycle of homelessness and incarceration: People who have stable housing are less likely to end up in jail, and people who have never been incarcerated are less likely to become homeless. Nonetheless, City officials have proposed to invest heavily in law enforcement rather than in adequate access to housing and health services.

Through this year’s budget process, San Francisco has the opportunity to choose whether it wants to follow the national trend of criminalizing poor people, especially poor people of color, or invest in racial and economic justice. San Francisco has historically relied on policing as its primary response to poverty.

With adequate resources allocated to voluntary mental health services, deeply affordable housing, and free residential drug treatment, San Francisco could stop the mass incarceration of homeless people.