The route to the Snakepit homeless encampment is as circuitous as the name suggests. Taking Muni in any direction involves a stop requiring a 10-minute walk to Seventh and King streets in what’s now called the Mission Bay neighborhood. That trip concludes with a dead end that’s fenced off by the Caltrain line and shadowed by the Interstate 280 overpass.

This is — or was — the terrain that made the Snakepit one of the longest surviving camps while the City disbanded several other encampments throughout San Francisco.![]()

![]()

At least that was until October 19 at 7 a.m., when San Francisco police announced to the occupants of the 25 remaining tents and tiny wooden houses that they had to vacate the area.

Within an hour staff from the Department of Public Works and the SF Homeless Outreach Team arrived, as did observers from the Coalition on Homelessness, which publishes Street Sheet, and the Democratic Socialists of America.

There was some question about DPW’s “bag and tag” procedures when a worker claimed he would only collect a bag of a person’s clothes and a bag of medicine, but otherwise, the “resolution,” as the City likes to call the procedure, seemed to be a by-the-book operation. That hasn’t always been the case with other clearances, where workers don’t follow City rules requiring prior notice, leaving encampment residents displaced.

The Snake Pit is one of many encampments that has been “resolved” by the City’s Encampment Resolution Team. More than three weeks prior, yellow notices were tied to tents and poles around the encampment stating that people would be unable to stay past October 19. The notices also outlined services that would be provided, including access to the City’s Navigation Centers and treatment for substance dependency.

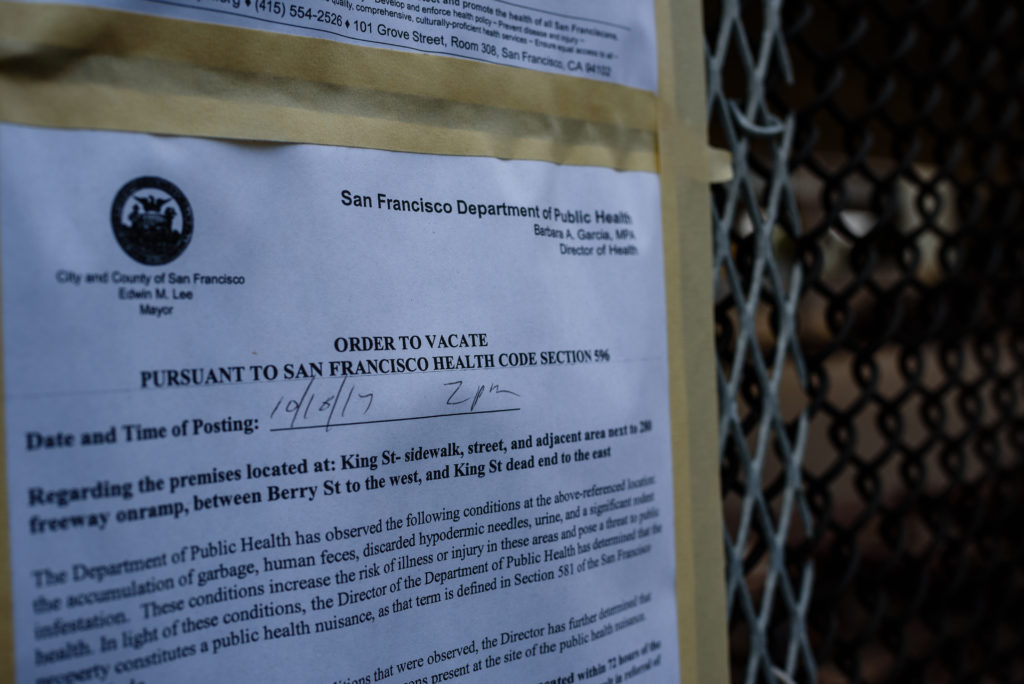

Another notice was posted on the afternoon of October 16. Per the City’s protocol, SF Department of Public Health employees posted 72-hour abatement notices written in English, Spanish and Tagalog. The notices cited Section 581 of the health code, declaring the Snakepit a public health hazard because of “accumulation of garbage, human feces, discarded hypodermic needles, urine and a significant rodent infestation.”

DPW staff brought a large trash compactor to dispose of the larger tents and accompanying furniture, while shoveling smaller debris into trash cans. But they were also dressed in coveralls that resembled hazmat suits. This apparently reinforces the “threat to public health” frame officials have been using to signal camp removals. It was also used to justify last year’s evacuation of a tent settlement on Division Street.

Most of the residents reported being already offered services, such as a bed in one of the Navigation Centers, before the camp’s dismantling. Still, that morning, two people didn’t have anywhere to go until Jason Albertson from the HOT Team made referrals on the spot. Albertson declined to explain further, citing medical confidentiality.

At least one other person, Street Sheet has learned, was running into delays in her Navigation Center placement. Former resident Sirena Gibson was about to get rid of her oft-overheating Nissan Quest.

“I was gonna give to the wrecking lot, but I’m glad I didn’t,” said Gibson, who was still staying in her car pending a call from the HOT team. She was supposed to start her 30-day stay at the center on October 23, but hasn’t gotten confirmation from her contact from HOT.

“She’s flaking out on me,” she said. “I don’t like it.”

But one question about “resolution” remains unanswered: Where do they go when their 30 or days or so at the Navigation Centers are up?

The resolutions have also underscored San Francisco’s ongoing gentrification saga. Most encampment clearances usually start with complaints from their housed neighbors and merchants, usually from calls to 311, and result in some contact between the camp dwellers and law enforcement. Since last year, other city agencies, such as the Departments of Public Health and Public Works, have also become involved.

Near the Snakepit, most complaints focused on car break-ins, discarded hypodermic needles and garbage. While it’s easy to pit condo dwellers making six-figure salaries against the less well-heeled, it has been residents of Crescent Cove Apartments, a below market-rate complex of 234 units abutting the encampment, who alerted the City.

Crescent Cove is a property that the nonprofit Chinatown Community Development Center co-owns and manages, and it sits near a growing design district in the Mission Bay neighborhood. The development center’s website says the building is “targeted for populations at 50 and 60 percent of rents in the area.” Curiously enough, it also sits in what real estate site RentCafé deems as one of the 20 most expensive ZIP codes in the U.S.: The median rent in the 94158 ZIP is $3,931 per month. If Crescent Cove units fetch rents in the $2,000 range, using those measurements, they would still be out of range for most homeless people on disability and other safety-net incomes.

By the afternoon, police barricaded the sidewalk — as they have with other former encampment sites.