The Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing recently released its Five-Year Strategic Framework. Outlined in the 68-page document are ambitious goals, including reducing chronic homelessness by 50 percent and ending family homelessness—all by 2022. We take a deep dive into the strategic framework. Here’s our analysis.

Coordinated Care

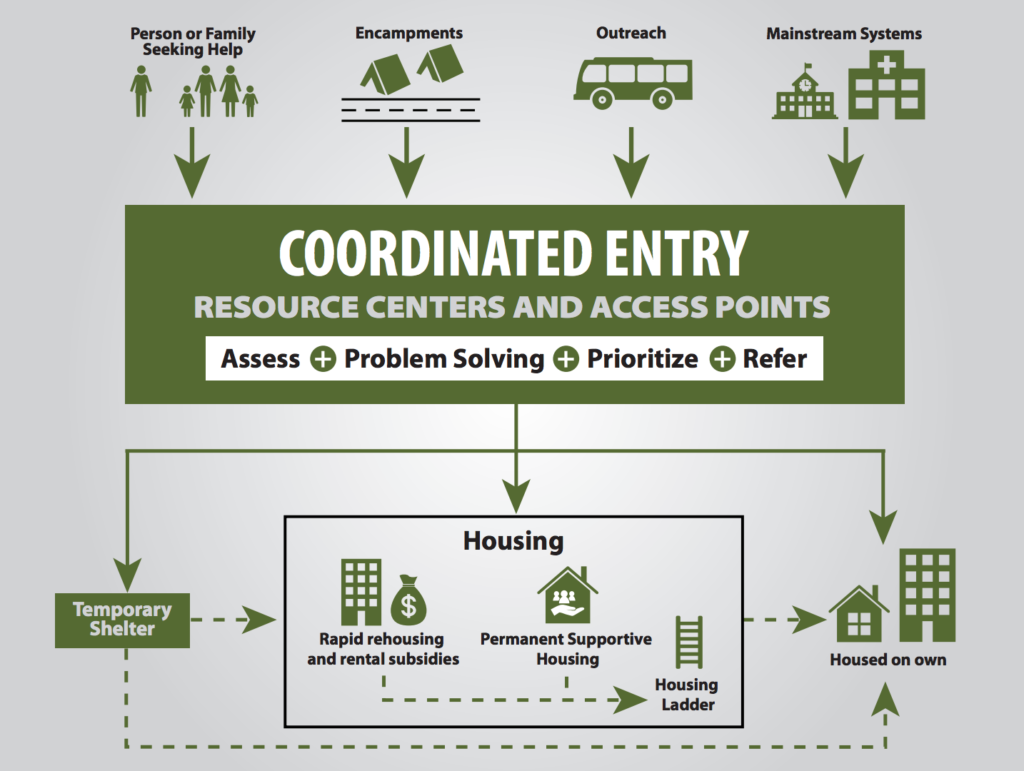

The cornerstone of the strategic framework is coordinated entry. The direction towards streamlined care, through a federally mandated process defined as Coordinated Entry, should prevent homeless people from having to runaround to different agencies as much as they do now. In essence, people experiencing homelessness would be referred to an “access point” where they would be assessed, prioritized (for example, veterans are the highest priority group amongst single adults), and referred to services. Coordinated entry is separated into three groups: youth, families, and single adults.

While coordinated care is essentially beneficial, many homeless service providers have taken issue to its implementation. Why? Some homeless families—those who are not San Francisco residents, families who are “doubled up” (living in a someone else’s couch or living room), and families living in Single Room Occupancies would be barred from key services. While these families will still be assessed and “problem solved,” they will not be prioritized for services or referred to services.

What would it take to end homelessness?

The most glaring problem with the newly released strategic framework is what they don’t say. For months, we’ve been hearing about how this plan was slated to outline unmet needs and the resources we would need to solve homelessness.

Apparently, the Mayor’s Office must have gotten their fingers on this and insisted it be a document outlining everything they are doing, not drawing attention to the many things they should be doing and aren’t.

We have right now a rare opportunity in San Francisco to seriously address this issue. We have the conditions that are needed to truly affect social change. Homelessness is more visible than ever: Everyone from renters worried about joining their ranks to owners of expensive new condos who don’t feel they should have to step over destitute people want to see change. At the same time, we have an untapped tax base that could easily provide the resources necessary to come as close as we can to ending homelessness here. The Department needed only to layout the need and we could collectively use that to fight for a revenue measure that pave the way home for thousands of San Franciscan.

Instead we got the usual puffing up of everything the city in its grand benevolence is doing for the downtrodden. Overestimation of their impact. Using the lowest estimate of need available.

They claim they have helped 25,000 people exit homeless since 2005. It’s important to note that the number includes thousands of bus tickets out of town. They also include turnover in housing units. That means if someone loses this housing and becomes housed again, they’re doubled counted and the City has now housed two people. The actual number of 7,500 housing units and 900 subsidies is great; it’s fantastic. But it is not 25,000.

The plan calls for 1424 housing units and/or subsidies over five years. They also call for 1500 prevented from becoming homeless and 800 bus tickets out of town (over five years!). We would love to see the city attempt to layout the reality for San Franciscans so they can see exactly what we are up against, and what it would take to solve the issues. This is not impossible but we must be clear on how to get there.

The City is doing a lot. They have a lot to be proud of. But it is not enough. A more insightful strategic framework would have clearly defined the gaps in services and housing and then created a clear plan to work towards meeting those needs.

How many homeless people are there?

The report relies heavily on the Point in Time count, a federally mandated report that count the number of homeless people on a single night in January. This past January, San Francisco counted an estimated 7,500 homeless people. It’s a notorious undercount. Yet the throughout the report, the Point in Time count is referred to, instead of the actual estimated number of homeless people who receive services annually. That number—21,000—is one that is used by the Department of Homelessness itself, and it’s the number we should be referring to if we actually want to know what it would take to end homelessness.

Families Left Behind

While the strategic framework clearly expresses ending family homelessness, the Dept. of Homelessness’ narrow definition of family homelessness leave hundreds of families out.

First, homeless families are also severely undercounted. While the report found that less than 3 percent of homeless families are unsheltered, it also mentions that there are around 2,000 homeless children in the San Francisco School District.

San Francisco defines homelessness for families as all those who do not have their own place to live and includes not just families in shelters and streets, but those living in hotels and motels, and families living on the floors of other people’s homes. The Dept. of Homelessness has already been using a much more narrow definition of family homelessness, leaving out families who are in hotels or motels or doubled up in someone else’s house. The Point in Time count only includes families in shelters, and a few who were identified as being on the streets. One can assume from the report that they are planning on ending family homelessness—but perhaps only for those who fit in their box.

They also plan to help 835 homeless families by “problem solving” in the next five years. Problem solving is to provide one-time support to people who can resolve their homelessness without the need of ongoing support. For example, a family could receive a small amount of money to say pay a utility bill so they can stay in their apartment. But for families who are living on the couches or floors of other people’s homes, reaching out to the city is a cry for help to get out of these situations. These families face severe hardship: There could be active drug use in the house, or parents being forced to trade sex for a place to stay. These families would also be left out of the main services from the Dept. of Homelessness and only be able to access “problem solving.”

Ending Homelessness

We want homelessness to end. We’ve seen tens of strategic plans, ten year plans, five year plans, and strategic frameworks to end homelessness. Plans are good—if they are realistic in identifying the actual needs of the homeless population and consequently working to address those unmet needs. We hope that the Dept. of Homelessness will let San Franciscans know exactly what we need to end homelessness and how we are going to get there. ≠