Since 2015, homelessness in San Francisco has decreased one percent. According to San Francisco’s just-released 2017 Point in Time Count, there are 7,499 homeless San Franciscans—down just 40 people since the previous 2015 count.

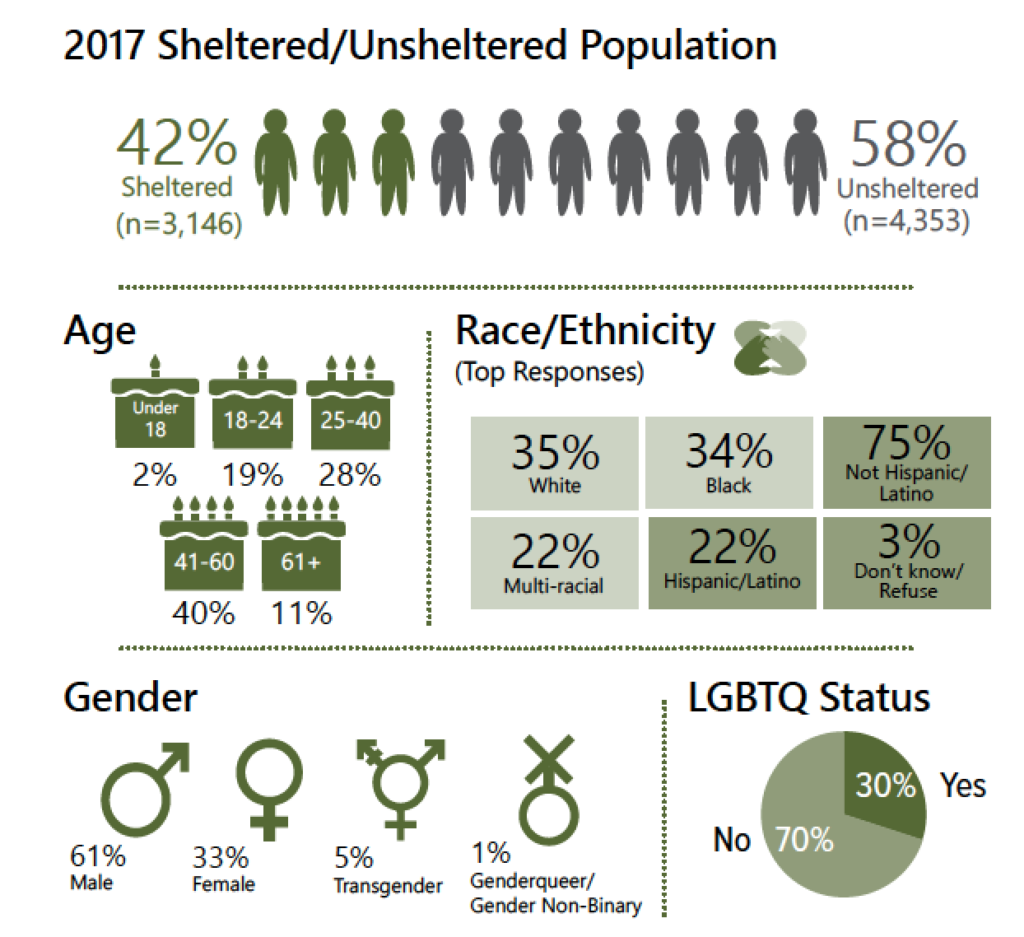

More than half of this homeless population is unsheltered. San Francisco’s adult shelter wait list has consistently been over 1,000 people since last year, leaving people to sleep in their cars, streets, parks, and abandoned buildings.

Marginalized communities were disproportionately represented in the homeless population. While African Americans represent 6 percent of San Francisco’s population, they accounted for 34 percent of the homeless population. Similarly, Latino and Native American populations had higher numbers in the homeless population than in the total population. Thirty percent identified as LGBTQ.

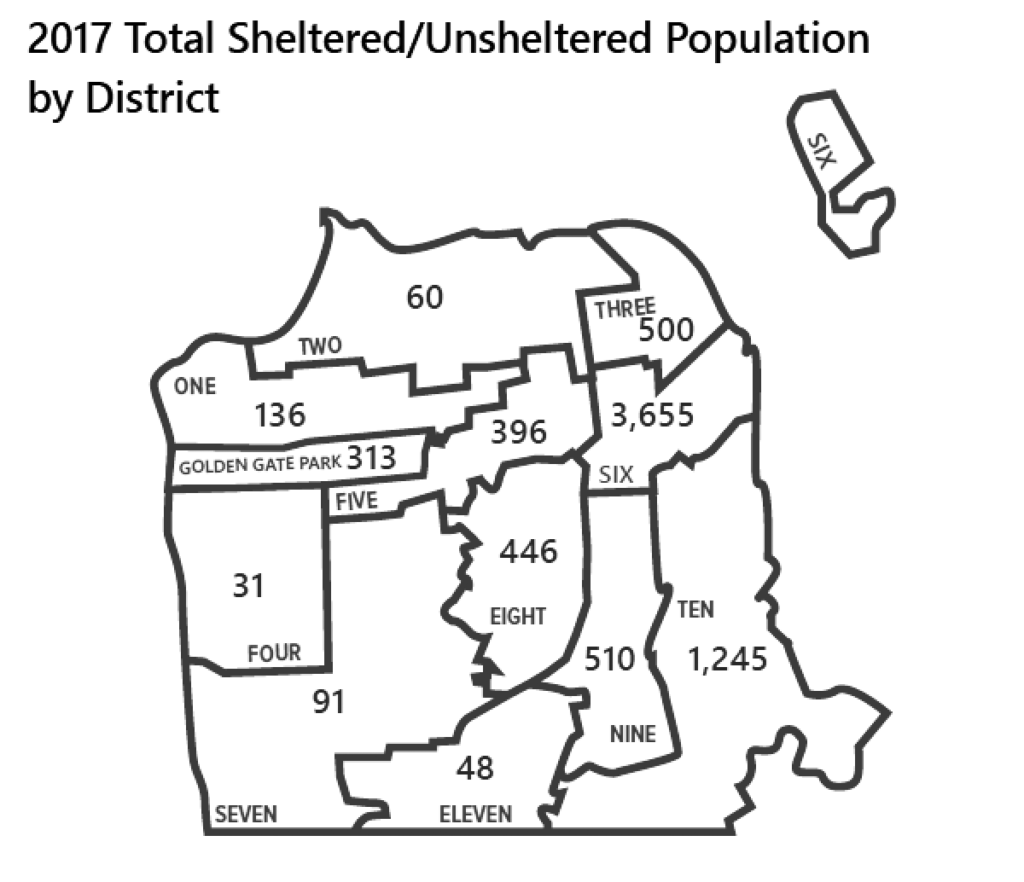

District 10, which includes the Bayview and Hunters Point neighborhoods, had the second highest homeless population, with over a quarter of the unsheltered population residing there. Despite having over 1, 245 homeless people, the Bayview only receives 7 percent of homeless services, illustrating a great inequity in the distribution of services.

The count also showed an eight percent increase—from 51 percent to 59 percent—in chronic homelessness, a clear reflection of the failure of the City’s systems to serve homeless people.

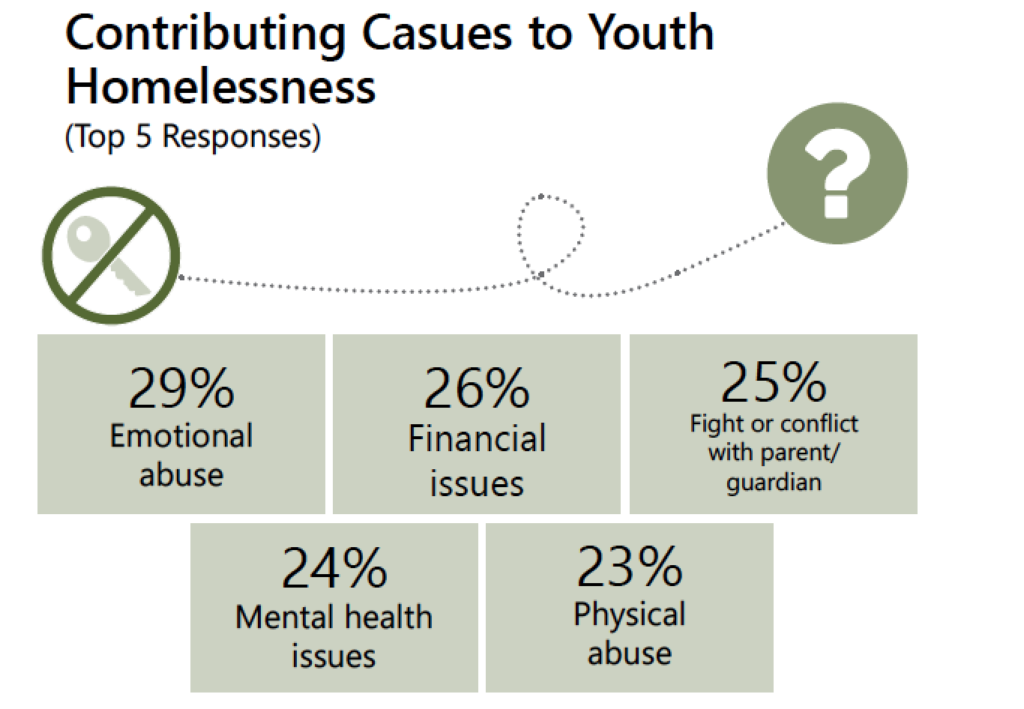

On the other hand, San Francisco’s youth count demonstrates that increased spending on housing and services can greatly decrease homelessness. Since 2013, youth homelessness has decreased by a whopping 28 percent, even when youth homelessness has increased in other major cities along the West coast.

Mandated by the federal government, the biannual report is often criticized by advocates who argue that its methodology does not yield results that are comprehensive or accurate.

There are two count methodologies. The first is a general street count, conducted in late January by hundreds of volunteers (This year, it was 750), from 8 p.m. to midnight that covers all of San Francisco. The number of people residing in shelters, jails, treatment facilities, and hospitals are also counted that same evening. The problem with the street count is that it is a visual count—it’s left up to each counter to determine whether or not a person they see on the streets is considered homeless. This also means that homeless people who are not visibly on the streets that day are not counted, including the multitudes of families living in other people’s living rooms or SRO hotels.

The second part of the survey takes on a qualitative approach: Homeless people are given the opportunity to conduct surveys to their peers that collect more in-depth demographic data and are paid $7 per survey. Still, there are problems with this. The surveys are limited to Spanish and English, excluding data collection on people who speak any other languages.

The Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing reports a much higher number than the official 7,499 count, saying that over 18,000 people cycled through its system in the last year.

But the count does dispel some longstanding myths, like the belief that San Francisco is a magnet for homeless people: Most homeless people (69 percent) were housed San Franciscans before they became homeless.

Alameda, Seattle, Portland, and Los Angeles’ Point-in-Time Counts all revealed increases in homelessness.

According to Jennifer Friedenbach, Director of the Coalition on Homelessness, “The combination of a continued lack of investment in affordable homeless-centered housing on the federal level and skyrocketing rents has led to huge increases in homelessness in cities across the West Coast.”

Still, advocates urge that a one percent decrease is far from success.

Says Friedenbach, “While San Francisco has managed to stave off those increases with investments to address particular populations, it is truly disheartening to call keeping the status quo a victory when so many are seeing their futures dim as they languish on our streets or in shelters. We still only spend 2.7 percent of our city budget on homelessness, and clearly have a long a ways to go to end homelessness in San Francisco.”

Clearly, San Francisco is need of greater funding and resources to start making a dent in ending homelessness. The stagnant numbers reflect the little that the City has put towards affordable housing and services—little more than 2.7 percent of a $10 billion budget was allocated for homelessness in prior years.