State legislators are proposing a host of changes to conservatorship laws that govern when people with disabilities can be institutionalized. While there are four different pieces of legislation being considered, one is getting a lot of play in San Francisco, and that is Senator Weiner’s legislation to change the definition of “gravely disabled” to include addiction, homelessness and frequent hospitalization.

We have a tragic history of violating the civil liberties of mental health consumers – both locking them up, and then by gutting our community mental health system, forcing them to live on the streets untreated. After abuse was uncovered, protections were crafted to strike a careful balance to ensure that disability rights were not violated, while safeguarding the individual who truly cannot care for themselves, or are a harm to themselves or others. As these solutions came out of a consumer movement, any changes to this law must come from and center around mental health consumers themselves.

It is important to remember that Mental health conservatorships, which are sometimes called LPS conservatorships because they are governed by the Lanterman-Petris-Short Act, can involve confinement in a locked psychiatric facility, which means the person is deprived of personal liberty. Therefore, there are strict legal procedures and laws that must be followed by doctors and hospitals and which involve review and monitoring by the Probate Court.

How it Is Now

Right now police or sometimes a licensed 5150 card holder can determine that someone is at risk of harm to self or others, or gravely disabled to the point that they cannot care for themself, and can then take the person to SFGH locked psych ward. The psych ward can hold someone for up to 72 hours and decide whether or not the person meets the criteria. Typically, a person held in this manner will be released back to the streets pretty quickly because there are no resources in community to send them to and they have stabilized.

If clinicians feel the person should be held longer because they continue to meet the criteria for conservatorship, they can request an investigation by the Office of the Public Conservator which is a division of Aging and Adult Services. If the Public Conservator agrees with the clinicians, they petition for a temporary and eventually permanent conservatorship from the Probate Court, which then assigns a public defender as well.

A temporary conservatorship cannot last longer than 30 days. At the end of 30 days, the Probate Judge considers the petition for the general conservatorship. Evidence supporting the petition is presented by attorneys from the District Attorney, Public Defender, and the person being conserved or others may testify. The public guardian must prove the proposed conservatee was ‘gravely disabled’ beyond a reasonable doubt. The stricter criminal standard is used because the threat to the conservatee’s individual liberty and personal reputation is no different than the burdens associated with criminal prosecutions. The definition of ‘gravely disabled’ includes both mental illnesses, and alcoholism, currently. However, alcoholism is rarely used to hold people around the state because there are no locked facilities available to care for alcoholics.

On the basis of the testimony, together with the report of the conservatorship investigator, the Judge will grant or deny the petition, or continue the proceeding at a later date. In most situations, if the person is granted conservatorship, they are placed in a locked facility. Again, there are no other placements available that are appropriate – for example supportive housing is unavailable, or does not have the necessary intensive services needed.

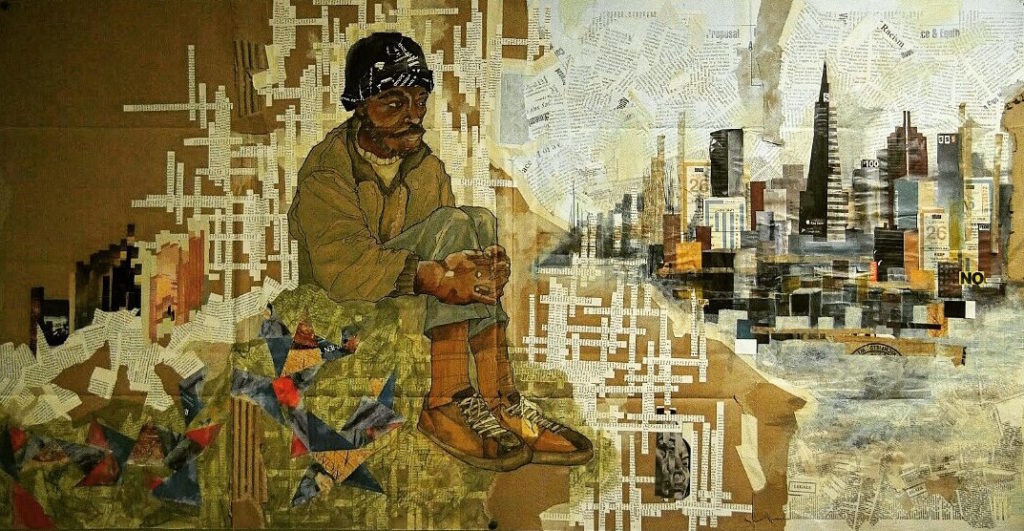

In most cases, the conservatorship could have been avoided if the individual got the care they needed early on. For many, the process is just more traumatic churning leading them further down the road of trauma and untreated illness – circling from streets to institutions and back to streets again. This will only change with a serious rebuild of our housing and behavioral health infrastructure.

What is Being Proposed

Senator Weiner is proposing to change the definition of “gravely disabled” to include homelessness, addiction, and frequent hospitalization. It is a spot bill and he has promised to get input, but going off what is included in the bill now, there are many issues with this approach. We will start with the big picture.

For decades, there has been movement to stop the over reliance on hospitalization in our mental health system. For a large proportion of the population, the very first introduction to care is in handcuffs, a locked facility and restraints on a bed. Traumatizing experience like these often discourages people from seeking care on their own. It is also very expensive, costing at thousands of dollars a night.

We have become so reliant on this high level of care because our community mental health system has been destroyed through state realignment which resulted in massive cuts, and a loss of about half of our board and care facilities. This coupled with divestment from housing on the federal level meant that many people with mental illnesses found themselves homeless. During the great recession, we lost over $40 million in direct services funding through the SF Department of Public Health (DPH) alone – leading hundreds of people to lose access to critical mental health and substance abuse services. For many more, the multiple traumas of living on the streets caused their mental health to disintegrate, and then led them to self-medicate with drugs and alcohol. Most experts agree that we need to invest in community mental health and rebuild our substance abuse treatment system so we don’t wait until folks are completely decompensated to get care.

While we eliminate care, our society has tended to then blame the people impacted by these losses. Typically, we focus on people “refusing care” as justification for criminalization or institutionalization. This also lets our policy makers off the hook and is a convenient election time refrain. That said, we never talk about the fact that most of those “refusing care” were never offered adequate services, and that even more salient, that the overwhelming majority of folks are trying to get care and can’t get it. When we have studied this problem, we have found that the problem is that homeless mentally ill and/or addicted individuals are “locked out” of services, not that they need to be “locked up”.

But let’s dig into Weiner’s proposal. He wants to add homelessness as a criteria that, if met, could justify conservatorship. Homelessness is not a disability, or a trait, it is a temporary state.

If this passes as currently described it would mean a person could be legally determined to be unable to care for themself because of their homeless status, creating a double standard that does not apply to housed people, and conversely applying to homeless people who are not mentally ill. Currently, the state of mental illness is what determines whether a person will be held against their will, so a person who is homeless AND mentally ill would meet that standard without adding in homelessness as a factor. Frequent hospitalizations would follow the same reasoning – what is it about being hospitalized in and of itself that justifies a hold? In addition, with the ability of the state to conserve someone comes a duty to provide assistance, but the plan lacks any funding to pay for housing, so people might be conserved solely because of their homeless status and then released right back to the streets. There is nowhere for them to go, and this bill doesn’t change that – it simple makes it easier to hold a larger group of people temporarily in hospitals.

When Senator Weiner introduced this bill, he talked a lot about the neglect of people on the streets, how it is not humane or progressive to leave them on the streets. True. It is also true that this bill will not change that and any false promises make it that much harder to forge real solutions. A stint in a locked ward or a bill that creates a hold in a place that does not exist does not demonstrate anything but continued neglect. As a society, we have immorally cut services and housing, and then we complain when we see people acting out on the streets. Our response should not be to make it easier to lock them up. This is a policy loop that will lead us nowhere. We need to jump off this cycle, and carefully, work together to craft solutions that work. And we know what works, it just takes real political will, not political games.