Since 2005, the Federal Department of Housing and Urban Development has required every city, county, state, or region that gets Federal money directly for homeless services conduct a count of its homeless people. While there’s a little methodological wiggle room, the basic requirement is this: That for a limited period of time on one night in the last week of January, the funding recipient send enumerators out into the streets and parks of the area and tally up every homeless person they can find.

In San Francisco, this has been a sight-only count (that is, enumerators don’t ask, “Are you homeless?” but simply mark a person down or don’t based on their perception of the person’s housing status). This point-in-time unsheltered count is then added together with the number of people staying in shelters, jail, and hospitals (the “sheltered count”) for a total tally of the homeless people in San Francisco.

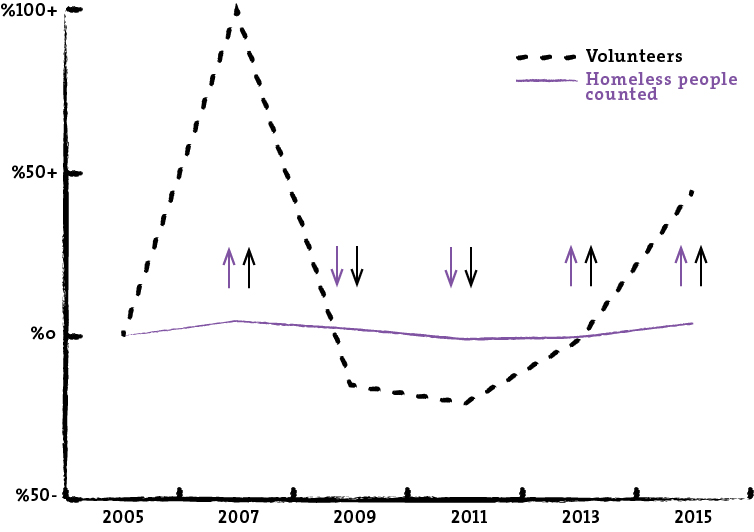

Almost universally, this number has been accepted as valid by the press. It is the number that news stories will use for the next two years when they wish to cite some number of homeless people for the city. At City Hall, the numbers have been used as evidence of the successes of various homeless policies. But at the end of the day, the number pulled from the Homeless Count indicates very little beyond how well the Human Services Agency has done at recruiting volunteer enumerators: Every time the number of volunteers has risen or fallen, the overall homeless count has done the same. What we’ve learned is nothing more than that 483 volunteers can count more homeless people than 425 can.

The problems in method are clear enough: No one—no matter how experienced, let alone volunteers—can consistently, reliably determine a person’s housing status just by looking at them. Because of the particularly intense criminalization of homelessness in San Francisco and the illegality of public sleep, a large portion of the homeless population tries to stay out of sight at night. And, of course, the count is going to miss everyone who’s not literally on the street at the moment—the people sleeping on their friends’ living room floors and the like.

And yet we’ve seen a glut of news stories and blog posts taking the count numbers as fact. The number of homeless people has nearly doubled in the Castro in two years! (Never mind that the same statistics show that it’s fallen by a wildly improbable 95% in the Outer Sunset, from 136 individuals to seven.)

The wackadoodle discrepancies in district counts and the positive correlation between number of enumerators and number of homeless people counted are pretty good evidence of the meaninglessness of the count, but particularly strong evidence comes in the count of children: According to the Homeless Count, in 2015 there were 463 homeless children under the age of 18. At the end of the previous school year, the San Francisco Unified School District documented more than five times that number of homeless schoolchildren. If you add in children below school age, the most reasonable estimate for the number of homeless children in San Francisco is in the neighborhood of 3,200. A portion of this is definitional: San Francisco’s definition of homelessness for City purposes is more expansive than the Federal definition used for the Homeless Count. But a 500% difference is not a matter of mere semantics.

The City and County of San Francisco has to participate in the count if we want to continue to receive Federal funding to pay for homeless services. But good public policy and meaningful public discourse cannot be fueled by bad research. Meaningful approaches to homelessness in San Francisco cannot be driven by the count. The numbers cannot be either celebrated as signs of the City’s policy successes or bemoaned as indicators of failure. We must do the count. But then we must acknowledge just how bad it is.