by Cierra Cardenas

Growing up in America during the height of globalization—and byproduct—capitalism has quickly shown me the dichotomy between human experiences as a result of a system that was built by many, to be enjoyed by few. I became aware of the classist formula of capitalism once I was able to experience its effects, both personally and from others who had seen sides of it I have never had to see.

I have been taught that in order to gain money for the things I need, I would have to work. But what was difficult to comprehend was that working would become my entire life. Just in order to get what I need, I realized I had to sell myself to a system that would perhaps eat me alive if I didn’t work fast enough. While I recognize the “advantages” I live with, I also never forget that privilege in America is a part of a system rooted in oppression. Privilege exists because oppression does. And I fear I have no choice but to comply. When did being able to pay for my essential needs become a privilege? When did having to work in order to afford your basic needs become normal?

There is not just one experience under capitalism. Most are silent about the particular ways they struggle under capitalism. Where there is struggle, there is absolute comfort and everything in between: You could have your basic needs met but money is always tight. You could be a student changing your community, but be drowned in debt. You could work long nights going overtime but be by the beach enjoying a vacation the next day. You could be over 60 and still have to work. You could be living on the streets. Struggle under capitalism looks different for every single person living in it, so what is your struggle?

Some days I feel as though I am living two lives under capitalism. One where I live as a laborer, submitting to people who have more in their bank than I may ever see, and another where I live out my passions and human experience, unapologetically. I see no end to a life of using my entire paycheck just to pay for a place to sleep at night. Why? Because capitalism is a system predicated on the subjugation of human beings, currently controlled by those with the money. It is a continuous usage of bodies to meet colonially imposed agendas and the desensitization to blatant authoritarianism (happening globally).Those with capital will continue to exploit people because they have the money to do so. But what happens to the laborer psychologically when they’re put up against a system with no promise of escape?

There are times I feel hollow because I know that this individual struggle will remain until catastrophic change occurs. I feel empty knowing that although there is validity in my own personal struggle, capitalism is unforgiving: If some have it all, others have nothing. My heart burns knowing that my immigrant father who has worked for his entire life cannot foresee a day where he retires because he cannot afford to.

Under capitalism, your essential needs come second to the money being made from them. You are profitable and your contract was signed years before you even existed. And, it functions by keeping us in our individual struggle or achievements, so much so that many forget to worry about their neighbor. But this is not just a system, this is our lives! I cannot help but wonder, when will I be financially able to retire…and live? I’m seeing double.

Seeing double, or “Double Consciousness” was originally described by WEB Dubois—a Black activist, scholar, and thinker who contributed valuable beliefs about the human condition under systems of oppression European people created and executed. In “The Souls of Black Folk,” Dubois discusses the psychological experience of having an African identity while forcibly participating in a European education, culture, and way of life. It is an experience—admittedly, completely different from my own—that sheds light on the overt abuse practiced on other human beings. As I pondered the idea of living a double life under capitalism I realized that DuBois had already explored what it means to unwillingly navigate a world that was not made for you to enjoy. How might Dubois’ theory of double consciousness help uncover how capitalism, among other oppressive systems, has infiltrated into our present psychology – creating a double consciousness of its own? Without eliminating the very real and powerful message specific to the realities of being Black and living with a double consciousness, I ponder how the conceptualization of a dual reality can be applied to other aspects of “modern” life. By exploring this, I do not intend to minimize the true origin of double consciousness as DuBois presents it, instead I inquire about how the idea of living a double reality—which affects everyone in different ways under capitalism—can be related to his words. Capitalism is our life, but it is not who we are. It begins our mornings and ends our nights, controlling how we live it. Double vision.

What is double consciousness?

Double consciousness comes second to what DuBois calls the color line. In Souls of Black Folk, DuBois remarks that “the problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color line.” The color line is the creation of the difference between Black, White, and everything in between. It is an ideological spectrum of categories that suggest one’s positionality and power, rooted in White Supremacy. It is more than an ideology, however, because it has been institutionally exercised and enacted on society. The color line is so strong that it creates what DuBois refers to as “the Veil.” It is a screen that shields how people see one another and especially how Black folks see themselves, one that is so blinding that Black individuals begin to see themselves through the eyes of others. Moreover, it’s an experience that white people create for others while never having to undergo it themselves. In turn, leading Black individuals to a double consciousness wherein they have to psychologically grapple with the world from two different perspectives. One, where they are themselves and another where their being is impacted from the racialized world around them. But it is not clear cut, nor is it easy to distinguish between the two identities. This is the problem for DuBois. More than the issue of racial difference, the problem is the psychological, mind altering outcome that continues to permeate through society.

So we see, double consciousness is in direct conversation with oppression and exploitation. In fact, it was born from it. As millions of African people were forcibly brought to foreign lands to work during the slave trade, they were subjected to physical and mental violence— a violence that projected a false reality of hierarchy onto human beings, that altered the mind, body and spirit, generationally. It is a struggle of finding oneself in a system that tells you there is no self to find. Double consciousness remains a vital explanation of how to confront African American identity and history, while also providing us with language to question how might this theory be applied to other Western systems of power (especially because America’s wealth was created off the labor of enslaved people).

Fundamentally, this framework is about the racialization of African people and white supremacy. Without stripping this vital framework, I wonder how it can help us understand our experiences struggling under capitalism. The way I see it, how we see ourselves and our identities under capitalism parallels the phenomenon of double consciousness Du Bois described. My labor is not my identity, but so much of my life revolves around labor that it mingles with the idea of becoming a part of it. It’s a condition that almost seems inescapable. The veil follows us wherever we go. How other people view you is a result of your veil: Do you appear to afford nice things? Have a nice house? Do you dress well? Are you educated? Do you have money? These are the questions we are met with, but the veil does all the talking. Moreover, these questions and the social connections that are created based on the answers trickle into the fabric of our beings whether we see past the veil or not.

Seeing Myself: A Reflection

At 19, I realized how being a laborer could become my entire future under capitalism. It was the first time I felt like I had two lives and realities to balance. Because, once I got to college my parents told me they could not afford to pay for me. Rent, food, and other basic needs somehow needed to be paid for.

As I write this I hear a voice in my head that says, “my anxiety about money is nowhere comparable to the experience of someone living with no shelter or warmth or access to food. I have no right to talk about this or even complain.”

I feel compelled to explain why this thought came to my head. We have become desensitized to the idea that if you are not houseless and hungry, your financial struggle is not valid. That is why I often feel like the conversation about capitalism is black and white. It often revolves around poverty vs. billionaires but rarely questions “what about the gray space in the middle”? This middle space sees a spectrum, from people comfortably living, to those who are surviving. Surviving can look like having absolutely nothing, to having just enough; constantly working to maintain it. While some have the privilege of receiving a university education (yet struggle to pay for it), others attend an under-resourced school that affects their ability to get accepted to a college in the first place. Neither of these realities should exist.

It is easy to devalue my financial stress because there are so many people that have less than I do. But the truth is, that people’s struggles can parallelly exist at the same time; They’re just different byproducts of this system. No matter what, no one should have to endure either of these lives. No one should have to surrender who they are because they have to work every single day, just as no one should have to live on the streets. But here we are, seeing double.

When I turned 19, my family went through a huge financial shift that forced my siblings and I to become fully financially independent. The anxiety of quickly having to be able to pay for myself as a young person living in one of the most unaffordable cities in the US, was debilitating. It is a reality where I have just enough funds to pay for myself but need two jobs in order to afford it. In this current reality, I am understanding what it feels like to survive. But I wonder how it would feel to live.

I cry because I know that I cannot quit or I will not survive. I cry because I see no end to a life of exploitative work, everywhere. I cry because we have willingly created and maintained a system that puts money over people. But I know that my tears are felt by millions as they silently cry themselves to sleep too. It is disheartening to think about the people who have to sacrifice their lives for an unforgiving system that sees their existence as profit. But as they take their last breath they rest knowing that at least they won’t have to survive anymore.

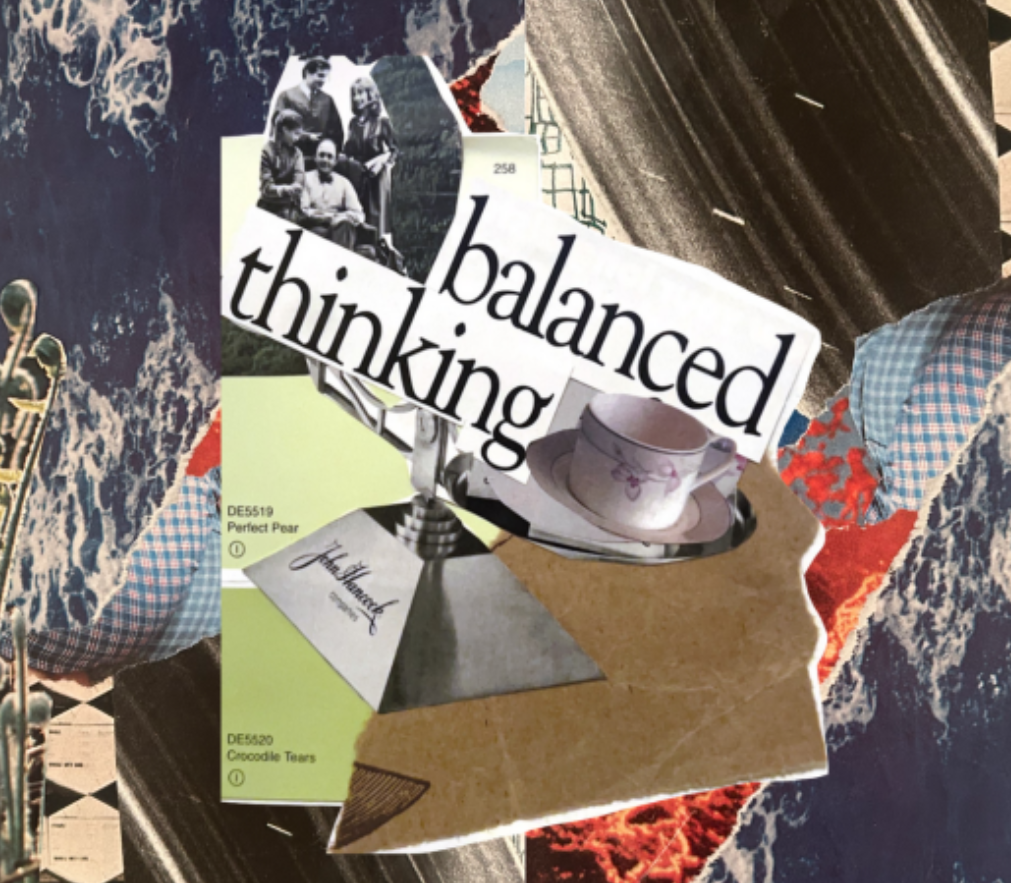

Image courtesy of Cierra Cardenas