As San Francisco considers arming its police force with Tasers for the fifth time, we explore the history of the electronic control weapon and how it’s worked out for other cities.

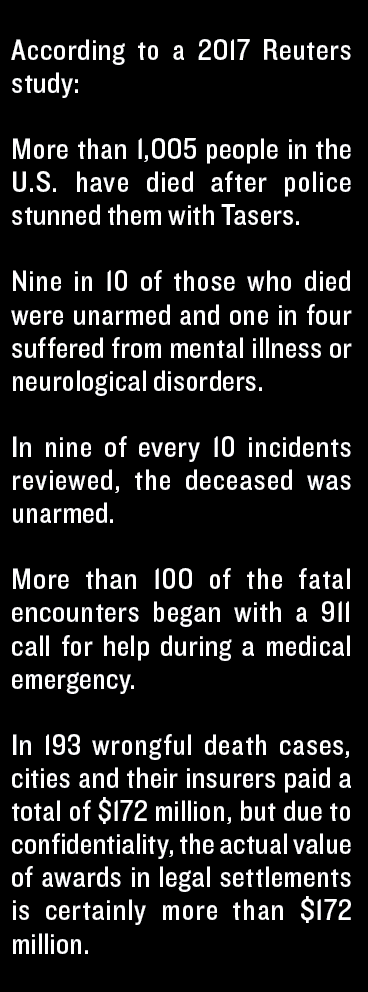

On September 28, a person in Oakland was shocked with a Taser after allegedly trying to flee a car crash scene, but died in police custody after the weapon was used and then taken to the hospital. There are a lot of questions surrounding the incident, and as a sensitive ongoing investigation, there’s no information on what crime he was being detained for, or if the cause of his death might be “excited delirium,” a very rare neurological condition that according to various civil rights advocates around the world, including the NAACP, is unusually high on the death certificates of people of color after a fatal police encounter such as this one.

Barbara Attard, the former police accountability auditor of San Jose, agrees that Taser, the only brand of Electronic Control Weapons (ECW) used nationally by any police department, as cause of death is often underreported, and research about its dangers on individuals in extremely stressful situations are often silenced. It happened to UCSF cardiologist Zian Tseng after publishing research on the relationship between Tasers and cardiac arrests, when he was contacted by Axon (formerly Taser International) to “reconsider, or even fund his future research.” According to Attard, the national push to arm police departments with Tasers is due to the lobbying and big spending that Axon has done, miseducating many to believe that Tasers are a safe alternative to other options, particularly in the face of recent media exposure of police brutality in the U.S.

However, San Francisco is the last major city left without arming its police department with ECWs. That’s unless the SF Police Commission votes for their approval this November.

“People don’t even call them weapons,” says Attard. “They are weapons. Tasers are deadly.” In 2005, after a year of being deployed in San Jose, Tasers hadn’t reduced the amount of police-related deaths and, according to Attard, “After Taser-related deaths, people began to request their removal from the city’s police arsenal.” She adds that Tasers are often used on individuals who have a mental crisis or are undergoing substance abuse, which exponentially increases their risk of death. Dayton Andrews, a human rights organizer at the Coalition on Homelessness, which publishes the Street Sheet, adds that “the research is clear that it is disproportionately used on people of color.” He argues that the homeless population will be the main target if they are deployed especially “now SFPD deals mostly with calls related to homeless people,” and says that “if you add the fact that a large part of the population has mental health issues, people of color, and being consistently criminalized there’s a real reason to think they will be at higher risk.”

But is it better to be shocked than shot? For Attard, that is another myth. “The fact is that in most police departments, officers are taught not to use an ECW or any ‘less lethal’ option if they’re confronted with a ‘deadly force’ situation,” she says. “Because the less-lethal option may not be effective, and the officer and/or a member of the public will be in jeopardy if the less-lethal option doesn’t stop the perpetrator.” In 2015, Taser deployments among Los Angeles were effective only 53 percent of the time. “If you had a car that didn’t work half of the time, you wouldn’t buy it, right?” Attard says. A police officer in Houston even filed a lawsuit in 2011 against the manufacturer, because the new model that she used, which was supposedly safer, led to paralyzing painful convulsions or death, and failed to stop someone whose actions ended up severely injuring the officer. The lawsuit accused Axon of making them less potent in the face of public outrage about deaths by their product, jeopardizing the safety of police officers, a fact that exposes the contradictions of this double-edged controversial weapon.

Even the official guidelines have changed since the creation of the weapon. Axon says that the weapon shouldn’t be targeted on the chest area, and even if the new version is less efective, it has more “darts,” or shots, so it can be used multiple times on a same individual. An individual that according to the latest draft

of the SFPD Electronic Control Weapons policy can be handcuffed, but only if “the subject is displaying an overtly assaultive or violently resistive behavior and lesser means have been tried and failed or would be ineffective.” It’s hard to imagine what a “violently resistive behavior” could be a threat in an already restrained, handcuffed person, other than the symptoms of excited delirium, such as “agitation, incoherence, bizarre behaviour, high temperature, superhuman strength, a high tolerance for pain — and sometimes, the compulsion to break or bang on glass,” Amanda Truscott wrote in 2008 for the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

The Coalition on Homelessness, along with other human rights groups and citizens of San Francisco, have been through this anti-Taser battle before. Indeed, the debate has been raging on since 2004—the fifth time in 13 years. The SFPD has been lured by the Axon corporation and the many studies that confirm the effectiveness, safety and quality of the new models, and the fact that the Sheriff’s Department and the BART Police already has them. For Andrews, that Axon has been pushing the SFPD for their implementation is “100 percent certain; they are the only major suppliers of ECW of every police department, and the research that supports their safety can be traced back financially to them.” On the other hand, those who have voiced their opinion in favor of Tasers think that cops need more options to handle different situations, that they actually prevent violence. Tasers with training would be fine, some argue.

However, Andrews judges that in meetings with the community, those who favored Tasers were a small minority, or “the type of people who call the cops if they see a homeless person in front of their homes.” He adds that the reason why the SFPD argues its need of Tasers is because “it is an intermediate force weapon between a baton and guns,”. But for Andrews, “de-escalation techniques, time and distance, is a real solution,” something which the officers, mental health advocates and social workers made up of Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) already implements.

Sheryl Evans Davis, executive director of The SF Human Rights Commission, says the concerns she has heard are the same: “Community safety, the significant death rate, perceived bias against certain populations [minorities], and how this replaces de-escalation.” The commission has organized the last two meetings between the community and the local Police Department, and in both there was an “overwhelming negative feeling” about arming the SFPD with something that is “not a tool.” She also said the commission will gather and supply feedback from other communities, including the Tenderloin, where the largest concentration of homeless population resides.

According to an investigative report by the Miami New Times in 2014, the local police departments in the Miami Metropolitan Area used their Tasers 87 percent more if the person was homeless, and a higher rate on people with some kind of mental health issue. The people who are more vulnerable to the deadly effects of Tasers have been targeted the most, because regardless of mental health, the inherent stresses of homelessness implies a risk for higher cardiac problems — the main reason why electroshock weapons can be deadly.

In 2016, none of the 22 fully reported deaths by Tasers was armed with a gun, and only one had a knife, according to The Guardian website “The Counted,” which tracks police killings and puts California at the top of the list. If Tasers are as safe as they are claimed — a 99.7 percent safety rate according to Axon — the only way those deaths could happen is if they are being used repeatedly for non-threatening situations, as it is stated clearly in most police guidelines (including the one recently drafted by the SF Police). But to kill anyone with that percentage of certainty, statistically near-certain to be impossible, it would take many strikes, or an extremely ill equipped police lacking the essential tools for de-escalation, such as letting time pass, establishing a safe distance and creating verbal rapport.

Davis says that the community expressed that Tasers go against the principle of distance, because 7-10 feet is not enough if an officer is uncertain of a potentially risky situation. Moreover, instead of calling for backup and keeping their own safety, the police officers will rely on a weapon that could likely push a person in distress into violence if it doesn’t work. This can be stopped, because the situations where Tasers are believed to be needed can be treated with expanding the CIT program that has already trained more than 700 officers, which is the Coalition’s recommendation to “make Tasers an non-issue.” In a letter to the SFPD, Coalition executive director Jennifer Friedenbach pointed out that Tasers cost more than $17 million, according to Oakland Police Department estimates.

Andrews explains, “It’s the Tasers, the constant maintenance, the supplies and the training, supervision, weapons testing, and the SFPD wants to arm every officer.” The money could be saved or redirected towards the CIT program, to respond to crises were the subject is “disturbing the peace,” even armed with knives. Instead of violence, there are ways to calm down and take a person into custody if needed safely without the need of electroshock weapons, such as ones that might end up being responsible for excited delirium, a diagnosis that isn’t recognized by the American Medical Association.

However, the community is afraid that all this opposition sustained over 13 years won’t be heard. That was ratified by Davis in their meetings, and by Andrews with the way the police has handled them, and it seems natural after this exact same fight to keep San Francisco one of the few cities without Tasers in the U.S. was already won in 2015. Andrews told The Examiner last month, “We get the impression the department wants Tasers and is structuring this whole fiasco to get Tasers, they’re not interested in leaving it open for opposition.”

The latest draft for the less-than-lethal weapons is available in the SFPD website, and has been revised supposedly including with the input of the community. It still mentions the use of Electronic Control Weapons for SFPD officers.

San Francisco became the last big city without ECWs after Detroit implemented Tasers a few months ago. A $50 million lawsuit has already been filed against Michigan State Police for the death of teenager who was struck and killed with a Taser while riding an ATV. ≠

The San Francisco Police Commission will be voting on use of Tasers on Friday, November 3rd. If you are interested in joining the Coalition on Homelessness in fighting against police use of Tasers, e-mail Dayton Andrews at dandrews@cohsf.org. You can find more here.