by Loretta Nicole Overton

Querida, te amo, they call us the Goonie generation—the ones who say “never say die.” The NeverEnding Story generation.

I’m writing this for anyone who has lost someone to the streets, to addiction, or to forgetting.

I’m writing it for the people who loved them anyway.

You had so many names. I’m going to call you Atreyu—the one who keeps going.

I still cry the same way I cried on December 12, 2001—because I couldn’t remember anything, and because ten years later you told me how you prayed to the Virgin of Guadalupe, and how I was the answer to those prayers. I couldn’t remember anything except that I loved you.

Not even how I wrote The Unwanted Fairy for your little sister, as a prayer for the happy fairytale I wished we could all have.

On October 4 last year—a day of deep listening—I went to hear The Halluci Nation. Somewhere between bass and memory, I remembered how the sound of the dogs in the Mousetrap game made me laugh uncontrollably as a kid. Only two people would ever know that. And you are one of them.

No one can tell me anything. I remembered, finally, on my own.

Playing dolls with Andrés, Marcella—and Ricarda. Gathering seashells. Everything felt like magic before the forgetting began.

In February 1979, Ricarda was killed in a fire with her mother, her grandmother, her baby brother and sister, and her unborn baby brother. I was four and a half years old. I wasn’t writing poetry then, but you were. You wrote a poem about her:

Friends are a special thing to have.

Friends miss you when you go away.

Several years later, I wrote my first book of poems and rewrote your poem, because you were my friend and I missed you.

In August 1982, I rewrote it again—the poem you wrote for me in 1979 after Ricarda was killed—narrating it through a fairy I drew, with a hand that trembled because of the Stay Puft Marshmallow Boy. I called him that because naming him directly was impossible then. He was not a childhood fear, but a continuity of harm—a conduit for evil who terrified me beyond speech.

In 2001, I couldn’t even speak this without convulsions.

Still, they questioned the authorship of my own trembling. Still, I wrote. Still, I remembered what is most sacred.

In 1981, two years after Ricarda died, I was dared to jump off a seesaw. They said if I was really her friend, I’d fly like Wonder Woman. I knew I wouldn’t. But I jumped anyway. I knocked out my teeth.

I had braces twice. My teeth are still crooked.

They are the record. They are the receipts. They are proof of how far I’ll go for my friends, for truth, for poems like prayers—and for a love I don’t need anyone to validate except God.

I have always missed you, even when I didn’t remember why.

It has been over ten years since the night you stayed at my house, in the years when I still did not know who you had been to me. I fell asleep with my head on your chest, listening to the soft thump of your heart. It was raining. You were slightly drunk, desperate for a cigarette, and you went into the bathroom to smoke. I was irritated.

Still, I fell asleep listening to your heart.

In the morning, my bed smelled like cigarettes. I was annoyed—so annoyed—especially when you blew up my phone in a panic while I was at work. You’d left your wallet and needed it back. It was Valentine’s Day.

I drove home after work to give you your wallet. Then I went on a Valentine’s date—not with you, but with someone who decided we needed to be just friends. He knew I still had a bond with you I needed to work through.

When I got home, my bed and bathroom no longer smelled like cigarettes.

When I found you sneaking that cigarette, you were hunched over and said, “I’m sorry.”

I was angry. Then angry with myself for being angry. There was something about how you were hunched—humbled, apologetic—that startled me. Your arms were thin. I knew you were going to the clinic, that you liked your counselor, that you volunteered at Glide. I also knew you were still chipping when you couldn’t dose or couldn’t pay clinic fees.

Six months earlier, you’d spent over a month in the hospital with endocarditis. You never told me everything—just that bad dope caused growths on your heart. When you got out, you used a walker. I know now it was because your back was broken. You had been beaten up.

You were unhoused. But you were never unloved.

Back then, I couldn’t remember our childhood history. Remembering meant facing things that were unbearable: a family burned alive, and the larger patterns of harm that shaped us.

We were both children caught in federal crimes, in very different ways. We had both been shot up with heroin in our femoral veins. It could have killed us.

Even so, we found resilience in the same ways. We focused on academics.

You inspired me. You went to Lowell, graduated in 1987 at sixteen, and then went on to MIT. School was how we survived. It was how we held onto the future.

You remembered everything. I blocked it all out.

And then something happened in the summer of 1989, when I was fourteen—something that shattered my ability to remember at all, until now.

I was brutalized again by the Stay Puft Marshmallow Boy.

Today, I looked at the page in my old confirmation Bible—the one I underlined when I was fourteen—and something inside me finally shifted.

Back then, I underlined the passage about forgiving enemies and praying for persecutors because I wanted so desperately to be good. I wanted to forgive the people who hurt me. I wanted to forgive things I couldn’t even name. All I had was God.

And I see clearly now: forgiveness was never the problem.

The problem was the way predators twist compassion and confusion into weapons. He knew exactly what he was doing when he exploited the values I was being taught. He took the very thing that made me a good child and used it against me, again and again.

None of this has ever been my fault—or your fault.

The shame I carried for decades never belonged to me. It was residue—the imprint of someone else’s violence on a child who didn’t yet have words for what had been done to her.

And yet, even with all of that, forgiveness kept returning.

It has been ten years since I was told that you died, and my grief has never left me. Recently, I keep smelling cigarettes—even though I don’t smoke, and you haven’t been in my house in eleven years.

I was told you died from an overdose of ethanol, heroin, and methamphetamine. The morning you died, you went to the clinic for methadone. It made no sense that you bought heroin—it didn’t even get you high anymore, and you finally had free access to treatment.

I wonder—not as accusation, but as grief reaching for coherence—whether something was injected into you without your knowledge. I hold this question as grief, not proof.

A part of me wanted to raise holy hell about why your death wasn’t investigated more. But it was. I got the call asking for next of kin on Good Friday, at sunset.

You died on April 2, 2015.

Thirty years to the day after the story I wrote in 1985 about the threat the Stay Puft Marshmallow Boy posed to all of us.

I didn’t understand that alignment then. I understand it now.

After you died, I wrote about wanting to do something irrational—like smoking a cigarette, or burning a box of Kleenex sheet by sheet, watching each soft square curl into ash.

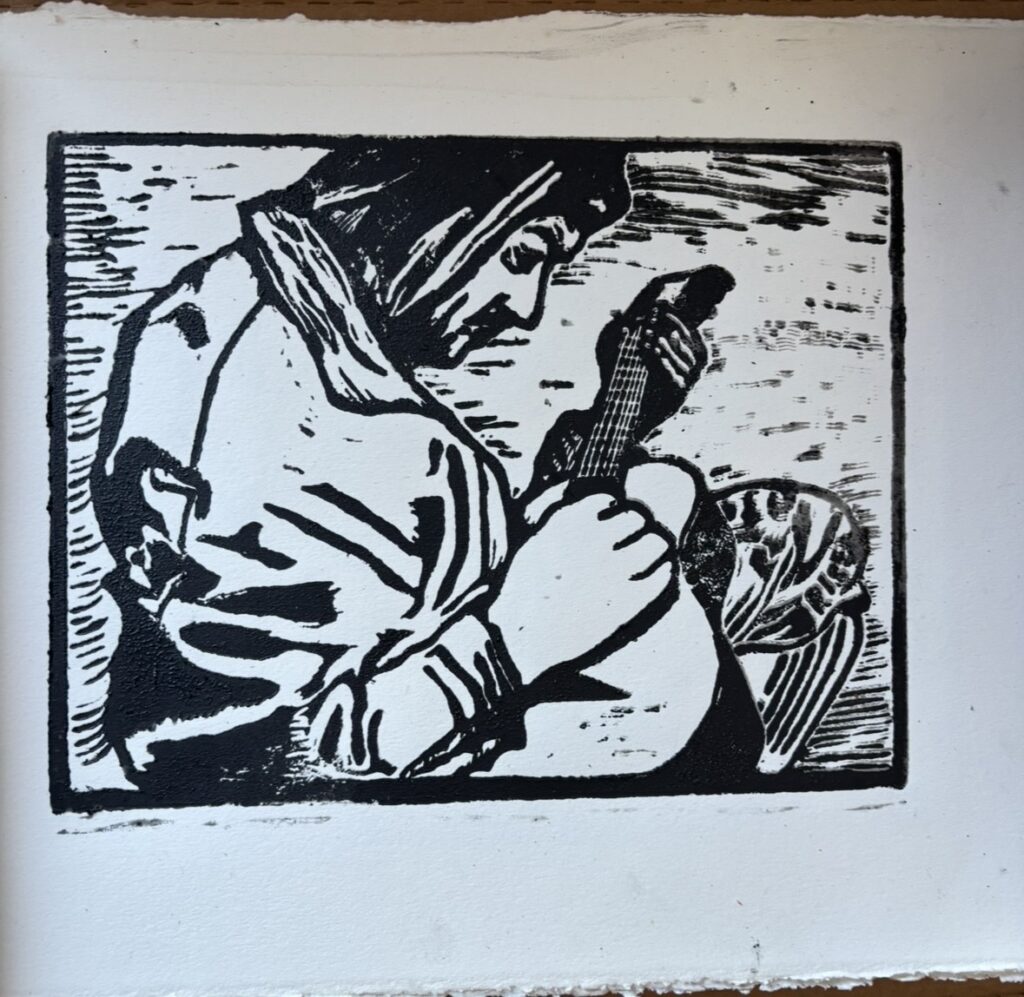

I’m haunted by your hands, by the burns from years of working in kitchens.

The first time you cooked for me was at home. You made a gluten-free pizza and refused to make the crust.

“I’m not down with gluten-free,” you said. “Pizza crust needs flour.”

I showed you the mix. “It has rosemary.”

You shook your head. “I’m sneaking flour in. I don’t care if it gives you gas. I’m compensating with real tomatoes and fresh mozzarella—the kind in water.”

Then you kicked me out of the kitchen.

You danced while you cooked. Your eyebrows were exclamation points.

“GET OUT!”

Later, you toasted pineapple so it wouldn’t be soggy. An hour later, you called me back.

It was gold and pink and red—something out of Chagall. The crust was wrong. Everything else was perfect. I swear I heard violins.

There is healing in memory.

Lately, I’ve been remembering the years around 1969 and 1970—things I heard long ago but couldn’t access until now. Disorienting. Clarifying.

This history isn’t just about us. It’s about survival. Mutual aid. Mutualistas. These weren’t theories—they were how people stayed alive when institutions didn’t care.

My tío said it best when he carved our names into a tree at Pinto Lake in 1976: it didn’t matter which God you believed in, as long as love was a verb.

When I returned there this year, I found Ricarda’s name still clear. Yours was barely visible. Mine had weathered into a heart.

There is so much more I’ve remembered. How deeply we were loved.

You lived with my parents for your first two and a half years. My mother didn’t care for you because you were unwanted, but because it wasn’t safe for your parents to do so. Protection, not abandonment.

Christmas 1973 was the first Christmas she didn’t have you—and somehow she became pregnant with me. A miracle she never expected. I understand now that loving you opened the door for my life.

Memory is returning in fragments: my name, Noel, conceived on Christmas Eve; a world shifting after Vatican II; danger for families who were Brown, Black, Jewish, Catholic, poor.

December 15 keeps resurfacing—César Chávez in jail, my grandfather’s death, a prayer book returned to me. Maybe your birthday. Maybe an anchor.

For years, I remembered nothing. Now I know for sure.

Your name was also carved into that tree.

You are who I married at Saint Patrick’s Church in Watsonville on September 24, 1989. You wore your MIT ring as a wedding band. You were eighteen. I was fifteen. We were married with a dispensation because my life was under threat.

So much was kept quiet to keep us alive.

I’m sharing this because memory heals—not by erasing pain, but by returning love to its rightful place.