An Interview with Leslie Dreyer

by Johnna Gadomski and Ella-Rose Kessler

“All good art is political! There is none that isn’t. And the ones that try hard not to be political are political by saying, ‘We love the status quo,’” – Toni Morrison (1931-2019), Rest in Power.

The world of artistic activism embraces the political nature of art, leveraging art to inspire thoughtful conversations, shape culture and drive new policy. Leslie Dreyer — an artist, housing justice organizer and activist — has been working with the Coalition on Homelessness on creative direct actions since 2015. This year’s Art Auction hosted by the Coalition on Homelessness will feature pieces by Dreyer.

“The idea is to think about how to use art for social political means to help people see something from a different perspective than [the] dominant norm,” Dreyer said in an interview.

Photo credit: Leslie Dreyer

Through projects like Stolen Belonging, First They Came for Our Homes and the tech bus protests starting in 2013, Dreyer has collaborated on and instigated creative actions that have epitomized how art and activism can harmonize to create important ephemeral community spaces and shift public conversations.

“I frame the work I do as tactical art organizing or art as direct action, because it merges direct action tactics, theater tactics, performance tactics, visual art and whatnot, for a specific goal to change our collective situation,” explained Dreyer.

Protesting in this way can engage and push culture in new directions, offering different methods of driving change. “Pickets and all sorts of protest are important,” said Dreyer, “but I do think art has a way of helping people feel more engaged instead of just reactive, especially if the audience may not be on the same political page.”

She commented on how “people are distracted and desensitized, to some extent, which could lead to them ignoring more traditional forms of protest.” Alternatively, art “has a way of making people sit with something a little longer to help them think it through or perhaps even see their own place in it.”

Creating a space for people to consider unconventional ideas through various art forms can help some foreign ideas become more digestible. Dreyer broke down a part of an action she worked on, which happened to be the first tech shuttle blockade. It was a prefigurative intervention–an action in which participants act out a situation performing the world that they want to live in, something that could be possible.

In this action, the participants were protesting the fact that the tech buses were using public infrastructure, like public MTA bus stops, to pick up workers commuting out of the city, while also spiking rents and evictions all around them. Objecting to tech-fueled displacement, the privatization of public space and how the tech companies take advantage of public infrastructure, they acted out a made up city agency, the San Francisco Displacement and Neighborhood Impact Agency.

“We wore yellow vest and acted like we were city workers enforcing the law that they were technically breaking… I calculated that if the companies had to pay a fine for every time their buses stopped, it would be approximately $1 billion, and we could use that for eviction defense or for truly affordable housing efforts,” explained Dreyer.

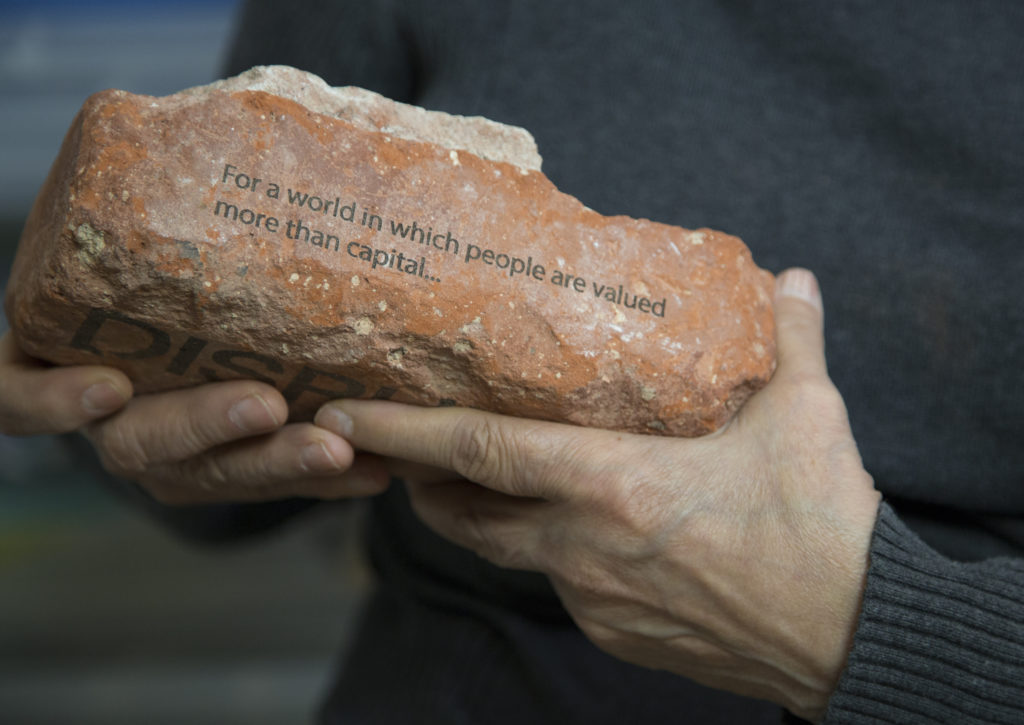

From the project First They Came For Our Homes, Together We Fight Back!

By performing actions like this one, performing what could be possible “people can more readily relate to the idea that this is not absurd, it’s actually something that’s totally possible,” she said. “It’s totally possible and urgently necessary for us to stop displacement and not give away our public space or infrastructure.”

In addition to inviting thoughtful consideration of what a better world could look like, creative actions that incorporate art can also set a positive tone and create a space for celebration and community.

“When you make an action more joyful–joyful and militant– and use art for more militant means to exert our collective power, it changes the way the participants, all of us, feel while doing it.” Pairing the exposure of injustices with the celebration of art and the community can powerfully communicate a narrative, while also inviting people in to participate in the movement.

“There’s music, there’s folks on the mic making demands in the face of power, and, for Stolen Belonging, for example, there’s real hard stories all over that DPW fence”.

At the Stolen Belonging action in June, the stories of DPW and SFPD stealing people’s survival gear, the ashes of their loved ones, their medications and more were on display across the DPW Operations Yard fence. Although the stories of these heartbreaking injustices lay at the center of the demonstration, the atmosphere was cheerful.

“We’re loving each other, we’re honoring each other’s words and we’re lifting each other up… people can connect to each other more when there’s art and music and poetry,” remarked Dreyer.

“Data doesn’t move people. It’s personal stories. It’s feeling connected to something and art helps do that,” Dreyer continued. “It helps people see things on a much more personal level. We can hear innumerable percentages, but until you put some stories and emotion behind it, make it beautiful, make it irresistible, then things may not change.”

Dreyer spoke to the increasing importance of using creative tactics to push social justice initiatives and campaigns. “I definitely think in movement spaces, people are starting to understand that art and culture are vital in the face of so much oppression and social control.”

The social and political climate of our world can be changed by artistic activism. “Cultural change is necessary to achieve political change. So you have to… move the culture, shift people’s ingrained beliefs and get folks involved to make them feel a part of it instead of isolating folks who may not be with us just yet.” Dreyer emphasized that it’s especially important to “bring people in… who’ve never been a part of movements, you know, or might even be on the opposite side of it. It is our work to try to bring people [in]”.

On September 12, the Coalition on Homelessness is hosting their 19th annual art auction at the SOMArts Cultural Center. The exhibition will feature over 200 art pieces. The narratives centered in these diverse works, all pushing for cultural change, are around homelessness and housing.

Dreyer will feature a brick from her “Reclaim Disrupt” project, which “took bricks from a San Francisco demolition site… then etched them with stories of folks who had been evicted, folks who had become homeless and also reasons why people are fighting for the city… the word ‘disrupt’ is also etched the opposite side of the brick.”

The purpose of using this word according to Dreyer was to “take the word back from the tech industry. They use it to congratulate themselves for disrupting or deregulating the market, when they’re actually disrupting people’s lives and livelihoods.”

Looking to the future, the powerful Stolen Belonging action at DPW was just the beginning. In the coming year, the project team — including COH members TJ Johnston, Shanna Couper Orona, Sophia Thibodeaux and Meghan “Roadkill” Johnson — will dream up more artistic actions. The team will also periodically release oral histories detailing the resiliency of unhoused folks in the face of theft and violence by the city of San Francisco, while reinforcing to larger movement’s demand to #StopTheSweeps!

To view or support the Stolen Belonging project, visit https://www.stolenbelonging.org.

From the project Stolen Belonging