by Nicholas Kimura

A giant Buddhist statue of dark obsidian-like stone dominated the altar, itself an impressive creation of dark, intricate woodwork spanning the entirety of the wall. Symbolic and ritualistic pieces of art lie, precisely placed and balanced, in their proper places throughout the sacred space. Rows of chairs perfectly aligned faced the altar in the bright, white room. To their left, a large set of windows looked out on the cold summer fog roll past Sutro Tower and down the hills of Twin Peaks. This was the unusual setting for a public SFMTA hearing. People were there to decide—or least give input—on the fate of parking in the Showplace Square district of the City, a meeting which, in the end, was as unexpected and unfamiliar as the center where it was held.

The Showplace Square area of San Francisco rests in the flatlands south of Potrero Hill and sandwiched between the northern Mission and Mission Bay. The square itself consists of large warehouses divided into smaller, high-end design studios and textile businesses. This area is also home to many people without safe, secure, and formal housing. Numerous individuals and families reside in this area in their mobile homes. Many others are forced to sleep outside—with or without a tent or anything to shield them from the elements. Because of this very visible contrast, homeless people living in vehicles and the street have become the targets of police criminalization and harassment from the Municipal Transportation Agency.

Several years ago, former Supervisor of District 4—the Outer Sunset—Carmen Chu, sponsored legislation to establish restrictions against the parking of oversize vehicles. The legislation passed, allowing parking restrictions to be established anywhere the MTA posts signs. Supervisor Chu, and her successor Katy Tang, have defended the law vociferously, saying it does not target homeless people living in vehicles but all oversized vehicles being parked in their district and “warehoused” on their streets. Despite our legislators’ claims, “oversize vehicles” is a euphemism for campers and trailers, namely those with people using them as a permanent home. People living in their vehicles have constantly complained about unfair treatment by the police and MTA workers, alleging explicit targeting of them and their vehicles.

District 4 isn’t the only area of the city where these discriminatory signs are posted. Neighborhoods including the Richmond, the Western Addition near the Panhandle, the north Mission, and the Bayview have all been subject to random, arbitrary placement of these restrictions.

The SFMTA has never been fully transparent with the process for how these signs are placed. Publicly, they have stated it remains a “complaint-based” system leading them to act. No data in terms of the number of calls received or the number of actual complainers have been released. Nor has the SFMTA indicated just how many calls it takes for a restriction to be posted. The result has been restrictions successfully moving through a bureaucratic process without any community involvement or the concept of a long-term, citywide strategy.

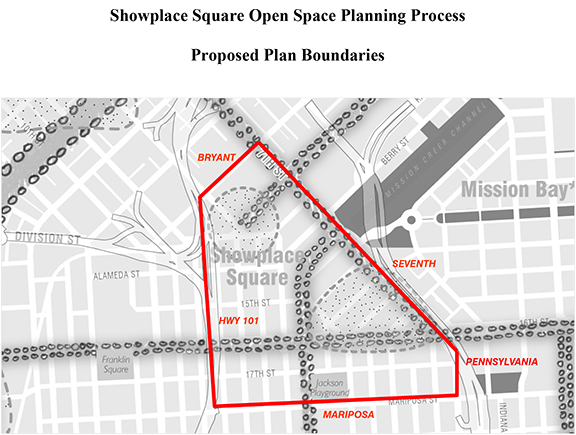

Given the chance to provide input in a public setting, several people housed in their vehicles bravely came to defend their right to rest at the SFMTA’s recent meeting. Hanging from the walls of the cultural center were large maps of Showplace Square adorned with colored lines running throughout the streets. One map showed the existing parking restrictions, appearing as a haphazard drawing where someone ran out of ink in their marker. There was little uniformity in the current restrictions with several types of restrictions—meters, hourly parking, and oversize vehicle—disjointed from street to street. The map illustrating the SFMTA’s proposal had lines connecting throughout the map with a sense of a broader plan. Oversize vehicles, however, were a primary target of the parking restrictions, with plans to post signs west, east, and south of Showplace Square.

This is when the first twist of this meeting occurred. Usually, community meetings surrounding homelessness include many people attending who seem to harbor the sole intention of degrading and humiliating those without housing in their neighborhood.

This time, however, many community members conferred and established three points for the parking in their neighborhood: (1) prioritize the “square” for hourly parking restrictions, (2) eliminate meters except for high traffic streets on the peripheries, and (3) accommodate those living in their vehicles with a safe space to park. The overwhelming majority of people present agreed to these tenets.

After a long, drawn-out meeting discussing various ideas of what parking should be, the community stood solid and kept their position to reserve space for people to safely park their homes. Granted the citywide rule prohibiting the parking of vehicles for longer than 72 hours and the city law against sleeping in your own vehicle still apply to all streets, the added burden of the oversize restrictions seems to be in decline.

Earlier in the summer, after many, many public comments by advocates pleading with the SFMTA Board of Directors to halt any more oversize vehicle parking restrictions, they finally listened and voted against future restrictions. Since then, they have not had any appear on the agenda or come to a vote. Seemingly another indication that these restrictions will no longer be placed at such a rapid pace with such a non-transparent process.

The community advocacy, however, is still needed. People living in their cars, vans, and RVs are targeted every single day in this city. Tickets are issued and at times peoples’ homes are towed away, rarely ever recovered by the owner because of the exorbitant fees.

Of greater concern, though, is whether the SFMTA will commit to the plans created by and for the community.

The people of Showplace Square recognized the ongoing housing crisis in San Francisco and respected a person’s right to occupy their own vehicle as a safe place to live. Because of this, they created a plan to accommodate oversize vehicles to avoid the constant criminalization and displacement they experience. This plan can be a remarkable incident of an inclusive plan created by those who live and work in the community.

It is now up to the SFMTA to respect the choices of the community or act as a divisive body between those with and without homes.