After months of moratorium on poverty tows, San Francisco may soon fall back on the inequitable practice.

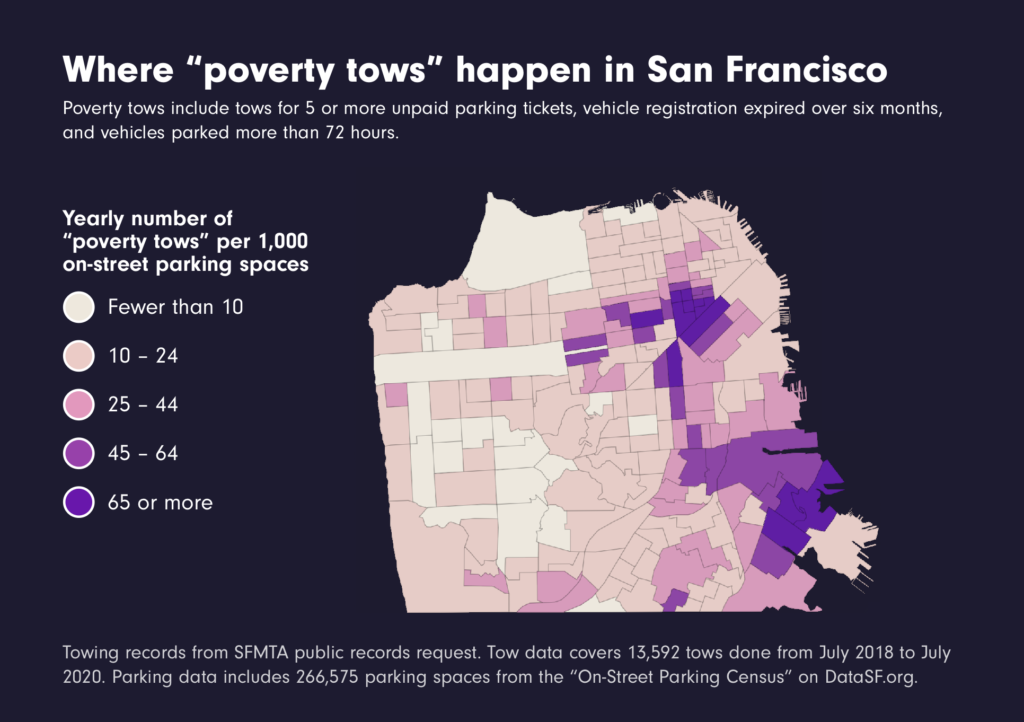

As the map pictured here makes brutally clear, the towing practices of the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency (SFMTA) are highly inequitable and disproportionately target San Francisco’s low-income communities of color living in the Bayview and Tenderloin. Welcome to the reality of poverty tows!

There are three types of poverty tows: tows for five or more unpaid parking tickets, tows for vehicle registrations that are more than six months out of date, and tows for legally parking in the same location for more than 72 hours. Based on information from an SFMTA public records request, Chris Arvin, a volunteer with the Stop Poverty Tows Coalition, compiled the data on poverty tows occurring in each district. Arvin found that 25% of all poverty tows happen in District 10, with a total of 3,405 poverty tows between July 2018 and June 2020. This makes it clear that residents of the Bayview are suffering most severely from these towing practices. Residents of District 6, which includes the Tenderloin and where 17% of all poverty tows occur, are the second most affected population in San Francisco.

The data speaks for itself. Poverty tows punish the most marginalized and vulnerable communities of San Francisco, and are particularly harmful for folks living in their cars or RVs. These tows result in tremendous and often undoable harm, as the chances of getting back a vehicle — or home — can be very low due to high towing and storage fees. And if the harm caused was not enough, the City’s tow program makes a deficit of $4.7 million annually, with low-income tows representing $1.5 million of this loss.

The pandemic brought an unexpected form of relief for folks living in their vehicles, when SFMTA halted these towing practices in early summer 2020 in response to the City’s stay-at-home order. This moratorium has meant great relief for many San Franciscans, especially for low-income residents who rely on their cars to get to work and other essential places, and most of all for those who rely on their vehicle for shelter.

After temporarily stopping the issuing of parking tickets when vehicles were not moved on street cleaning days over the summer, SFMTA resumed citations in September 2020. Since then, tickets and late fees have been accruing for vehicle owners who are still suffering from the financial hardship caused by the pandemic, and who simply can’t afford to pay the staggering tickets.

The Stop Poverty Tows coalition — endorsed by more than 70 organizations — is meeting regularly with SFMTA staff to advocate for permanently ending poverty tows and installing less onerous ways of collecting debt, among other harm-reduction practices around towing and citation. Despite this exchange, SFMTA has told the coalition that it is considering ending the moratorium on poverty tows in the coming months.

As for the 72-hour rule, cars that remain parked in a legal spot for three days may start to be towed again as soon as May. When asked why, SFMTA staff have referenced the “immense pressure” from other constituents and complaints about abandoned vehicles. Since the agency has not shared data or estimates on how many of these abandoned vehicles exist, it’s hard to say how legitimate this concern is. Regardless, it’s a sign that the complaints about the unpleasant sight of an abandoned vehicle voiced by some trump the risk of losing shelter for others.

It seems that SFMTA does not recognize that not towing someone’s RV or car — someone who is most likely already under financial hardship — is a form of harm reduction. The agency has a responsibility and opportunity to prevent people from descending into yet another level of poverty and homelessness. It’s a role that the agency seemingly does not want to reckon with.