Dec. 15, 2017

Dec. 15, 2017

by T.J.Johnston

The topic of homelessness is often addressed as an economic, health, or safety issue. But a special investigator from the United Nations came to San Francisco on December 6 to hear from community members with a take not often heard from officials in the U.S.: the human rights of homeless people.

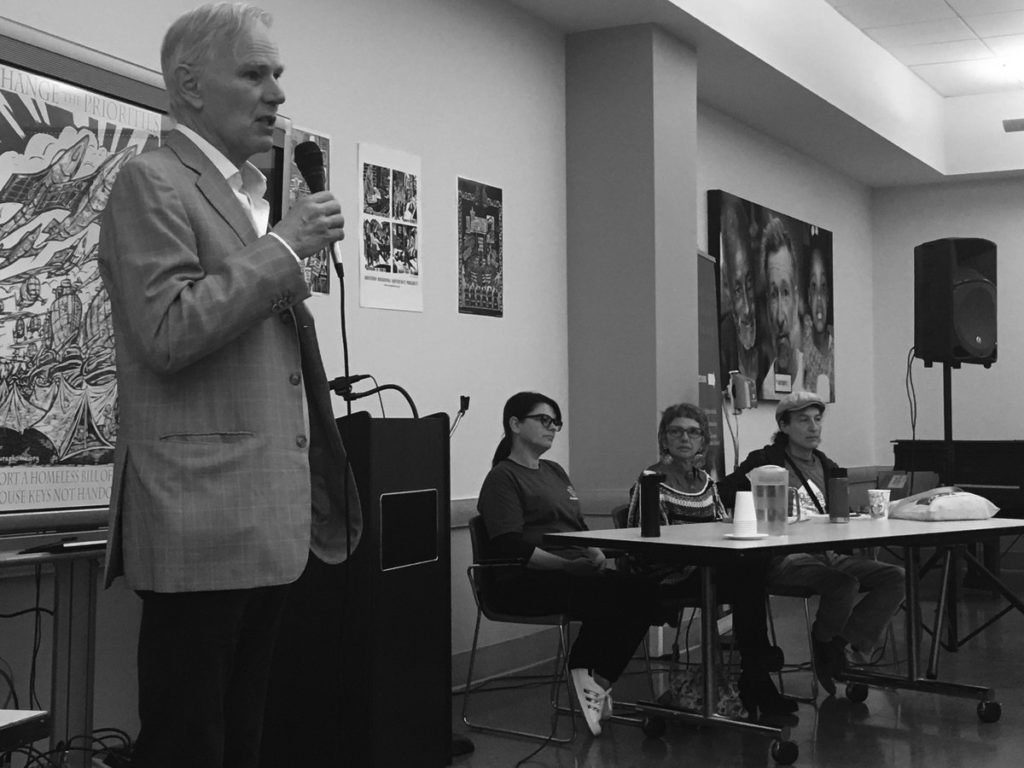

Philip Alston, UN special rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, visited San Francisco as part of a two-week, fact-finding mission throughout the nation. On the afternoon of December 6, the Australian-born law professor from New York University visited homeless encampments in the South of Market district — including one where a DPW cleaning crew and police paid an unannounced visit — but that morning in a special forum at St. Anthony Foundation in the Tenderloin, he also received input from several service providers and advocacy organizations.

The forum’s hosts included the Western Regional Advocacy Project (WRAP), a San Francisco-based homeless activist organization; St. Mary’s Center of Oakland; St. Anthony’s; and the Coalition on Homelessness, which publishes Street Sheet.

It’s in his capacity as a U.N. special rapporteur that Alston is visiting several American cities — he already visited Los Angeles’ Skid Row — to prepare for a report to the U.N. Human Rights Council in Geneva next June. He has scheduled a preview of his recommendations and preliminary observations on December 15 at Washington, D.C.

Alston also represents a body with a special historical link to the city: The U.N. was founded in San Francisco in 1945, and a plaza less than one-half mile away — a gathering place where outdoor markets and poor people commingle — is named for the international organization. In drafting its Declaration of Human Rights, the U.N. said that all human beings are entitled to food, clothing, health care and housing, among other things, to ensure their personal dignity as much as meeting their basic needs. The U.S. was one of 48 member nations that adopted the declaration.

Alston emphasized that the lack of such necessities of life — in the U.N.’s birthplace no less — violates the spirit of the declaration.

“Homelessness is not only a denial of the human right to housing, but it is also directly linked to the undermining of a range of civil rights,” he said in a statement before the forum. “The reportedly high levels of homelessness in San Francisco and other parts of California and the United States are therefore of particular interest to me in the context of my mandate to explore the links between extreme poverty and human rights.”

Extreme poverty — as the federal government defines it — is living on only $2 per day, a condition which is where 19.4 million people nationwide live, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. It’s likely that the 4,300 unsheltered San Franciscans who comprise more than half of the City’s homeless population meet that standard.

Some of those impoverished folk go to St. Anthony’s for free services such as its dining room and medical clinic, which they might be unable to access elsewhere. That day at St. Anthony’s, a series of panelists from about a dozen service providers and poverty advocacy organizations brought forth a range of issues — these included the impacts of gentrification and displacement, as well as the criminalization of poverty and homelessness.

Those are issues that directly affect the growing number of the City’s have-nots, according to Theresa Imperial of WRAP.

“As more and more of our communities gentrify and displace more and more of our neighbors, it is vital that we speak with one voice, with our collective human rights at the core of what we say,” she said.

After each panel presented its findings, Alston peppered them with questions. He asked what the Bay Area’s new arrivals, i.e. employees in tech companies, could do to stem gentrification. Tommi Avicolli Mecca of the Housing Rights Committee replied that wealthy people, such as investor Ron Conway, could easily raise $1 billion to establish land community trusts and co-op housing. Mecca also told him of a meeting with Conway where he bounced the idea off the self-styled “angel investor.”

“He just looked at me, told his assistant ‘talk to this guy,’ and walked away,” he said.

The police-centered approach to homelessness was also criticized in this session. Dilara Yarbrough, a sociologist at San Francisco State University, presented figures from a study she co-authored where a majority of homeless and marginally housed residents said they were often ordered out of public space by the police, creating what she called a “constant spatial churn.” Her research also showed that they mostly got ticketed for so-called “quality of life offenses” and jailed when they can’t pay. The City later stopped issuing bench warrants for people who don’t answer citations in court.

Complaints of homeless visibility often drive complaints from merchant organizations, said Shelby Nacino and Daisy Quan, who study law and public policy, respectively, at the University of California, Berkeley. These groups form business improvement districts that effectively privatize public areas and hire security to exclude homeless people.

Nacino and Quan also noted that since 1910, California cities enacted almost 500 laws that restrict homeless activity, from sitting on sidewalks to sleeping in vehicles.

When Alston asked what he could recommend in his report, Yarbrough suggested that cities “get rid of laws that make it a crime (for homeless people) to be in public space.” Some cops who were interviewed in the study deemed quality-of-life laws ineffective, and are reluctant to enforce them. Quoting an officer, Yarbrough said, “If Mrs. Smith calls 911 on a homeless person, we are duty-bound to respond.”

Alston also asked if the City had a strategy to expand housing for low-income populations, citing a recent voter-approved bond in Los Angeles as an example.

Jennifer Friedenbach, director of the Coalition on Homelessness, said a sales tax measure that narrowly lost in 2016 could be revived next year. Thanks to a recent court decision, she added, it could pass with a simple majority instead of the two-thirds the previous version needed, but fell short of reaching.

WRAP director Paul Boden, in a rabble-rousing moment, said homelessness can be ended with a systemic overhaul and people organizing. Lobbying organizations like the American Legislative Exchange Council push for neoliberal economic policies, such as tax breaks for wealthy homeowners at the expense of social service programs, he said.

“When we demand and when we push back, we kick ass and we win,” Boden said.

“It’s good to see an angry white male on the panel who’s not on the far right.” Alston said, wryly.