Visual art has served many purposes throughout history and across cultures, from personal expression, storytelling and creative imaginings. Art isn’t just drawings and paintings, though—it is spoken word, prose, poetry, music, dance, performance, sculpture and more. However, visual art, perhaps more so than any other medium of art, has been able to successfully utilize nonverbal communication to transcend socioeconomic and accessibility barriers for self expression and discourse. In the 20th century, artists increasingly began to use visual art as a medium for political purposes, or to criticize an aspect of society. In this article, we will be looking at public art, specifically the city’s street art which is highly visible, accessible, effective and a ubiquitous form of public expression.

San Francisco in particular has long been an important home to a myriad of artistic movements, styles and purposes, and has been a hub for all types of artists both known and unknown, professional and amateur. Naturally, publicly visible art has long flourished in SF, and a large part of the works in the city are murals, which can be found along the sides of buildings and walls in every neighborhood. Frequently, these murals are funded by the city or other private (or corporate) sponsors in an effort to beautify and support the communities in which they are placed. For example, the Coit Tower murals were created as a part of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal Public Works of Art Program, a program dedicated specifically to put artists back to work and invoke a desire for creating more works of public art. Other pieces, such as the Clarion Alley Mural Project, or CAMP, are collaborative efforts from many San Franciscan artists, including local community partners and youth initiatives, typically displaying politically charged messages alongside aesthetically pleasing scenes. There are murals all over the city, including Balmy Alley and the Women’s Building, which are interesting and impactful to both locals and visitors. In the same vein, Diego Rivera’s mural at San Francisco City College is representative of a larger movement of street art which tells the story of the inhabitants of the city, paying homage to minority groups and depicting historically significant events. And just as visible in the city as murals are messages like “NODAPL” (pro-indigenous peoples’ rights, anti- oil) that are tagged onto the sides of mailboxes and bus stops to make a statement. These pieces are not only important as representation and storytelling devices, but also as channels of effective public communication.

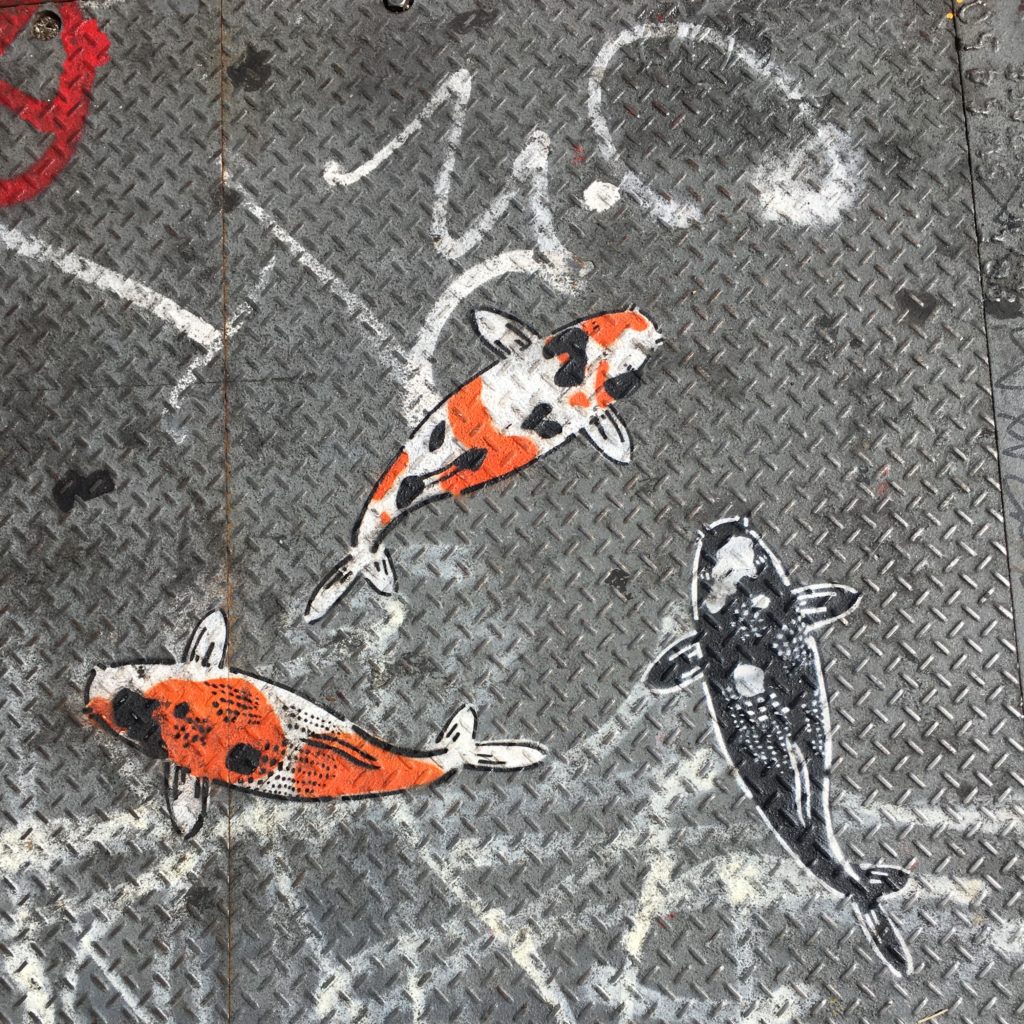

While it manifests itself in a multitude of different forms, and while there has always been controversy around it, street art is one of the most accessible and pervasive forms of public art. Ranging from more simple and quick pieces such as graffiti and tags, to much more complex and large scale works, street art comes in countless varieties and styles, each reflecting the individuality of the artist, and often, their roots and the culture that raised them. Though they can be commissioned, the majority of street art is generally considered vandalism and seen as a social ill, which are painted without permission onto publicly visible walls, bridges, trains and buses. Whether or not a piece of art is a direct call to action, it can invoke emotions that give agency — political or otherwise — to its audience. This is well manifested in satirical pieces (such as anti-Trump cartoons and statements), but is also a powerful tool of more abstract art pieces.

Although many popular murals are done by single artists, there are a myriad of murals painted by groups of community members for the beautification of the area. In recent years, along with the rise in the cost of living and ever-changing demographics in SF, more commissioned graffiti or “gentrified graffiti” pieces are being funded by wealthy newcomers and corporations, which are negatively viewed by the established area where the art is displayed. While appreciating and paying for a personalized (and often private) installation of a long-standing form of street art is one thing, some of these artists are painting over previously existing, culturally important murals and replacing them with placating, non-motivated pieces.

A large differentiation between street art and its gentrified counterpart is that the latter is typically (continuously) preserved, since it is usually paid for by those who can afford the maintenance, whereas its predecessor lives in an ever-changing state, adapting to the needs of its artists and the communities they represent. Self-titled “urban artists” such as Sirron Norris and fnnch, who are visible contributors to San Francisco’s public art landscape, put emphasis on “aesthetically pleasing art” to cover up “ugly” public spaces and try to distinguish themselves from graffiti/street art and tagging. These artists are also concerned about preserving their art and ownership and “protecting” it from other artists covering over/tagging their work, which is ironic, since the majority of these works are displayed in public spaces which are fair game to taggers and graffiti artists alike. While the preservation of one’s art is a reasonable thing to strive for, art which is tone-deaf to the community it exists in is ultimately disrespecting the culture which laid down a foundation for artists like them to even exist. Furthermore, organizations like 1amSF are teaching these gentrifiers how to tag, and offering tours of highly marked areas of the city, almost fetishizing the culture of street art while simultaneously appropriating it. This causes considerable upset in the affected neighborhoods, and the artists are regularly met with backlash, whether it be through counter-tagging (anti-gentrification graffiti) or social media. There just seems to be a significant difference between works that are a result of a labor of love for one’s culture and history and their frivolous counterparts, and San Franciscans not only notice but are passionate about it, on both sides. Only time will tell the fate of public spaces in the city, but for now, enjoy the view. ≠